Hide

hide

Hide

William James Slade

(1892-1982)

= = = = = = = = = =

The following is a verbatim transcription of a series of interviews made with Captain William James Slade, of Appledore, North Devon, and broadcast by BBC radio on three successive weeks in August 1962. The text has been transcribed word for word, however certain words were indistinct, but has been done as accurately as accurately as possible. Transcribed by David Carter 2018 |

|

|

= = = = = = = = = =

Programme no. 1

= = = = = = = = = =

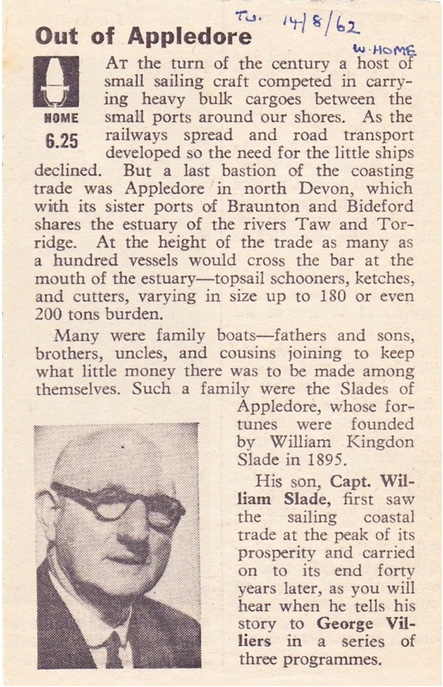

ANNOUNCER: 'OUT OF APPLEDORE'

The story of a British coasting seaman in the last years of the wooden sailing ships.

Captain William Slade of Appledore talks about his life to George Villiers who also introduces the programme:

INTERVIEWER:

Appledore, with its sister ports of Braunton and Bideford, was the last bastion of the small sailing coasters. Coasters which carried heavy bulk cargo; coal and gravel, grains and fertilisers, bricks and cement; in fact anything that offered. Sometimes trading even as far as the Irish and French ports.

Those were the days before the network of roads was built and before modern transport was even imagined. At the height of the trade as many as 100 vessels would cross the bar outward bound on one tide. Topsail schooners, Schooners, Ketches and Cutters, varying in size up to 180 or even to 200 tons burden.

Many were family boats: fathers and sons, brothers, uncles and cousins joining to keep what little money there was to be made amongst themselves. Freights were low and competition keen. Longshore labour was a luxury, and it was the crews of the vessels themselves using their hand-winches, and primitive tackle who loaded and unloaded the cargoes, as often as not, on an open beach so as to avoid paying harbour dues. Fortunes weren't made in a day, though hard work and frugality, enterprise and persistence, could bring their reward; and perhaps more than competence to the men and women of Appledore.

From such a family came Captain William James Slade. More than 40 years at sea have left bodily scars on Billy Slade, but not on his memory, as I found when I asked him to talk to me about those early days.

CAPTAIN SLADE:

My grandfather was always deep water, and he was illiterate, but he had two brothers that rose to be mates of Yankee downeasters. Being illiterate he got as far as being bosun of a ship, but no further. Then by and by, he married my grandmother - she was called Elizabeth Kingdon, he'd met her once in Bristol, she was a lady’s maid there.

How he got to know her I don't know, but he must have fallen deeply in love because on one of his return voyages, he walked the 110 miles to Bristol from Appledore to see her. Of course, that was in the 1830s, and (no, about 1840s I should think) and there was no means of transport you see.

Well eventually he married her, and she came to Appledore to live - in poverty, but she couldn't sit down under it. She had a marvellous character, and plenty of go in her, in fact she ruled the family like a queen. I can remember as a youngster - sitting in the armchair giving her orders, and she used to sit in a black satin dress, with a white hat on and a gold chain round her neck, she seemed to me to be the finest lady that was ever known.

INTERVIEWER:

Was it her that bought the first of the family boats?

CAPTAIN SLADE:

No. The one that bought the first of the family boats was her eldest daughter: Mary Anne. Of course - born in poverty, but my aunt (Mary Anne), she couldn't sit down in poverty. After, she married a deep-water sailor - George Quance, he spent most of his time in the tea clippers, but he was a very fine sailor. He could do anything with a piece of rope, wire, and he could carve a model, and he could make a sail, and after he'd finished rigging a ship - he could paint her - make an oil painting of her.

INTERVIEWER:

Yes, now you say in poverty Captain Slade, but you don't buy a vessel, even a small coasting vessel, out of poverty.

CAPTAIN SLADE:

But I'll tell you how the money started to come in. My aunt had learned her trade as a dressmaker in Bristol among her mother's friends. She came to Appledore, and when she married George Quance, she settled down to her trade as a dressmaker, and in doing this she never spent a penny of her husband's earnings.

He was inclined to be rather wild among his boon companions you know, and he didn't know anything about the money matters. She was just saving up for what she'd got in mind. He stayed home on the coast, and was mate of a brigantine, finally got master of a little small coaster, trading on the Cornish beaches mostly, and in the Bristol channel, and of course she kept on saving his money - whatever he earned.

But one day he came home late for lunch, and she took him to task over it - she was capable of doing that too, because she'd got a will of her own. Well, he said to her: "Well, I've only been having a drink or two with my pals - there's nothing wrong with it."

"No, (she said) but there's something I've got to do for you, and if you promise me that you'd back me up in every way, I've got the money to buy you a little vessel of your own, so that you'd be independent of everybody.”

Well he was rather taken aback. He said: "Well where did you get the money?"

And she says: "Does that matter, as long as I have it?" and he left her with the same.

The next day he went over on board his ship, and he came home early (for a wonder), very thoughtful, and he said: "Look here Polly ('cos he used to call her Polly, you know), what you said yesterday, you'd got money to buy a little vessel. Do you mean that or are just leg-pulling me?"

She says: "I mean it".

And he said: "Well it appears to me 'tis time I pulled my socks up, and I'll make you a promise that if this little vessel is bought for me, that I will see that she pays.”

Well the outcome of that was that they bought a little French ketch called the NOUVELLE MARIE. He worked her, and he did good work, in fact he made something of a record, with being the only sailing vessel that ever discharged three cargoes of coal in one week, from the Bristol Channel, and it's never been equalled since. Time went on, he still continued to do very good work, with the NOUVELLE MARIE, and she still continued at her work as a dressmaker always saving; by and by she bought her own house, and she bought one or two other houses, and of course they were bringing in the rent you know - it all helped, and she never touched a penny of it, just saving all the time.

INTERVIEWER:

So, you can really say it was your aunt and your grandmother who really founded the family business of shipowners.

CAPTAIN SLADE:

Yes, my grandmother after a time, she'd put her boys to work in the boat, when grandfather stayed home; she bought her own house, and then she saved money enough, to put in ships. But afterward…

I think the NOUVELLE MARIE was bought in 1888. It was 1896 that my Uncle Tom was out of a berth: he'd left his vessel after a disagreement with the owner, father was master of a little ketch called the FRANCIS BEDDOE at the time.

The HEATHER BELL (she was built at Barnstaple - and belonging to the Isle of Man), she came in the bay to come in over the bar, and she struck the south tail. She'd beaten off of the south tail, dropped into deep water, they got her in, discharged her, and they said: "She must be broken all to pieces in the bottom". They put her in on the hard beach outside the dock, and nobody would have anything to do with her.

My father thinking about his brother I suppose and spending a little bit of money that they'd saved up, he went on board. He always had an eye to a ship - even as a young man. He sounded her all over, he hammered her floors (the floors are timbers in the bottom of the ship), and he couldn't find anything broken in her. So, he went back to his mother, and persuaded his mother to buy this little ship. Of course, there she was in her damaged state as everybody thought, and his mother said: "Well, are you prepared to spend your little bit in her?"

He said: "Yes, I'll buy a quarter of her,"

And mother said: "Well I'll buy the rest - if you can risk your little bit, I can risk mine."

INTERVIEWER:

Now, from these really rather modest beginnings Captain, at the height of the family fortunes as shipowners, how many vessels had you in the family?

CAPTAIN SLADE:

I should say there'd be eight or nine all at one time. But of course, down through the years they had 22 altogether, then some would be lost and would be replaced, and then some would be condemned and replaced, but all together they owned 22 down through the years.

INTERVIEWER:

So you really built up a great enterprise from the modest beginning of these two wonderful women.

CAPTAIN SLADE:

Oh yes, that's quite true.

INTERVIEWER:

Now, a little bit more about your father: I understand he was illiterate too.

CAPTAIN SLADE:

Yes.

INTERVIEWER:

Even though he was illiterate himself, he sent you to school?

CAPTAIN SLADE:

He didn't send me, 'twas in the days of... education was compulsory, in those days.

INTERVIEWER:

Ah yes. And what school did you go to?

CAPTAIN SLADE:

Just an ordinary day school.

INTERVIEWER:

Did your father think that you were wasting time learning to read or write, did he want you to come to sea with him as a boy?

CAPTAIN SLADE:

He didn't want me to read or write – he used to throw the books overboard if I tried. I had to do it on the quiet you know. I used to hide the books away that I wanted to read, and I read all right, but he didn't know it!

INTERVIEWER:

When did you first go to sea?

CAPTAIN SLADE:

Oh, I was only three months old, in my mother's arms – that was before I could remember.

INTERVIEWER:

And did your mother go to sea with your father?

CAPTAIN SLADE:

Very often. She used to take her baby with her, of course she'd got other children, but they were looked after by one of the family. She always went with father when she could in the summer, and I don't remember much about it until they bought the ALPHA.

INTERVIEWER:

And that was the first ship that you went to sea in?

CAPTAIN SLADE:

The first I can remember. I was carried on board her, I was five when they bought her, and I can remember being carried on board on my father's shoulders, and I can remember being at sea in her, I must have been about six then, without mother.

INTERVIEWER:

What sort of accommodation had an old vessel like the ALPHA?

CAPTAIN SLADE:

Well, a small cabin, with a stateroom (that you couldn't swing a cat in), and a bunk that would... two could lay in it.

INTERVIEWER:

And what more? Was there room down forward for the crew?

CAPTAIN SLADE:

Yes, and there was a stateroom the opposite side from the master's, that the mate... where the mate's bunk was. But the cabin was separate.

INTERVIEWER:

And where was the galley, where was the cooking done?

CAPTAIN SLADE:

In those little vessels, in the forecastle. When I went to sea to work for a living, there was a separate galley on deck.

INTERVIEWER:

And when your mother went with your father, did she do the cooking?

CAPTAIN SLADE:

I'll give you an instance of what my mother was capable of doing: Father was in Lydney in the FRANCIS BEDDOE, he wanted to load a cargo for St. Agnes (that's on the Cornish coast), the crew had finished to go because it's a wild place; of course father was after money, he didn't mind where he went as long as he was paid for it, and the crew left and went home. He wrote home to mother, and asked her to send him on a mate, and she turned up herself. She stepped aboard and he said: "Well, couldn't you get anybody?"

She said: "I didn't try, I can take the vessel home with you."

And so they left Lydney. They'd got a boy there, a little tiny boy (about 12 or 13 - something like that), but they left Lydney, and mother took her watch at the tiller in those little vessels it used to be, but she could steer all right, and take her watch (father would be about you know), but she'd steer for four hours without any trouble; and she could box the compass, she knew every sail aboard. I remember her saying that they anchored off Cardiff, waiting for tide; father went to bed, mother had to keep watch. So when the vessel was swinging on the ground, you know - the turn of tide, she got her foot on the bow chain, and she felt something dragging over the ground. She went down and woke father up, she said: "She's dragging her anchor."

"Oh, (he said) I know what she's doing, she's dragging her chain round, you needn't worry about that."

So he got up, they got under way, and they came down the Bristol Channel, and they right got home - almost as soon as the crew got home.

INTERVIEWER:

I think that's a wonderful story.

CAPTAIN SLADE:

Well that's mother! But I remember once going with mother in the ALPHA and we went down the Bristol Channel, and when we got down to the Smalls (that's on the Welsh coast), there was a strong northerly wind; short-handed, father'd only got the mate there and mother and myself and my young brother - little kids together you know. We were on the quarterdeck when she took the sea on board and shifted the wheelhouse - that was the first start. So I can remember all the lee side of her underwater, and father was carrying on a press of sail you know, and mother said to him: "Billy, you should take that gaff topsail in you know, if you don't - you're going to lose your topmast. I'm telling you, you should take it in!"

He said: "I'll be across in Waterford before dark, she's got to have it today."

Well, it wasn't about two or three minutes afterwards before she was a total wreck aloft. It all came down, and she said: "I told you you'd do it!"

Anyway, we two children were bundled down in father's bunk, and mother went on deck to take the wheel, while father went aloft with the mate to clear away the wreckage, but they got to Waterford before dark.

You know, my memory is pretty good at that, because when we got to Waterford, I remember they had a new topmast. The topmast was 30 feet long, and cost 30 shillings, but he carried THAT away on the way back! (laughter)

INTERVIEWER:

I wonder what she said to him then?

CAPTAIN SLADE:

Oh, she didn't take any notice, she was the only one that could handle him at all. (laughter)

INTERVIEWER:

He was a rather great character your father, I take it.

CAPTAIN SLADE:

He was very very hard, in every way.

INTERVIEWER:

To his children, as well as to the men?

CAPTAIN SLADE:

I had to toe the line, and nobody on board the ship dared say anything to him, there was no back answers, when he gave an order, they had to jump to it!

INTERVIEWER:

And that went for his sons, or nephews, or whatever?

CAPTAIN SLADE:

Everybody. Mother was the only one that could talk to him. I never knew him laugh in my life.

INTERVIEWER:

Really!

CAPTAIN SLADE:

Very dour, you know, and mother used to sit and look at him across the table at home, and she'd start laughing, and he'd say: "What is she laughing at, what's the matter with her?" and the more he said that of course, the more she laughed, she was just laughing because he was so... he couldn't laugh then. She had a wonderful sense of humour.

INTERVIEWER:

She seems to have played him like a trail of fish rather!

CAPTAIN SLADE:

Yes, I remember years afterwards when I was mate with him, we were running up the English Channel, and we'd got the mackerel lines over the stern, and I hated salt mackerel, but of course if he could catch them, we had to feed on them.

Well, mother knew I didn't like it (she was there), and she used to get up four o'clock in the morning, (and father's watch was below, four to eight you see), I had to put the lines out as soon as it came dawn you know in the summer like that, and mother said: “If you don't like mackerel, what do you want to catch them for?"

"My word, (I said) if he was to come up and find me without the lines going, there'd be the deuce to pay."

She said to me: "I'll tell you what to do, you go down and get a salt one and hook on, come on, you do as I tell you."

So I did. I went down and hooked on a salt mackerel, and he was always in the habit as soon as he came on deck, of going over to feel the lines you know, he came up about quarter to eight, he said: “There's a fish on this line."

Nobody said a word. At last, (he's pulling it in you know) and when he saw the mackerel come above water, he said: “This fish has been dead for hours!" (he'd been dead for a week!). But he pulled it in, threw it in on the deck with a flourish, and all the time grumbling, he said: “You're too lazy to do the bit of fishing when you've got a chance."

And when it fell on the deck and he looked at it, I made a bee-line for the rigging - I knew what was coming you know. He nearly caught me, but I was up in the rigging before he could get there. He followed me up in the rigging you know, he said: “You've done that." and I thought I was for it you know. But when he got up to the eyes of the rigging, I was half way across the jump stay - he couldn't catch me up aloft.

INTERVIEWER:

I think you were rather lucky you know, 'cos I rather think you deserved it didn't you?

CAPTAIN SLADE:

Well I did, but then 'twas mothers fault really, but I didn't give her away. But all the time that father was chasing me, she was splitting her sides, and shouting to him: "Tis a dead one you've caught Billy!" (laughter)

INTERVIEWER:

Captain, when you first went to sea...

CAPTAIN SLADE:

I went to sea to work for my living after leaving school at the age of twelve - pass an examination and leaving school. Father came home from Teignmouth (in South Devon) and I was ordered to pack my bag and away I went to Teignmouth. When I got there, of course I started on my duties as cabin boy and cook. I had to learn it all of course, but it was coming.

INTERVIEWER:

What was the sort of routine of a boy in one of those ships?

CAPTAIN SLADE:

A boy was supposed to get up before anybody else in the morning, get the fires lighted, get the breakfast, and that had to be done in between working cargo. After breakfast he'd clear up the mess in the cabin and then get on deck and get the dinner going. All this time the rest of the crew would be waiting to start working cargo again. They would have had a sit down and a smoke, but the boy didn't get a chance to have a smoke even if he was allowed.

Well after dinner was under-way (that's the mid-day meal for sailors), he went on the winch with the other chap. If there was a moment to spare in between, up till dinner time he had to run to the galley - put in coal, see to his dinner and a hundred and one things that had to be done to get things going. Dinner time was the same old thing, he'd hurry up, wash up the dishes and if there's any moment to spare, there'd always be a little job for the boy to do.

INTERVIEWER:

And as the rest of… [break in recording] …that was how many?

CAPTAIN SLADE:

As far as the ULELIA was concerned, (that's the one that I went in first), she had the Captain, mate, A.B. and me. Well then as time went on, the A.B. went ashore and an ordinary seaman was shipped; as I got more able to take my place you see, and then finally the other ordinary seaman was put ashore, and I took the place of the third hand and we didn't carry any more.

INTERVIEWER:

Captain, were you very seasick as a boy?

CAPTAIN SLADE:

Oh, awful! The first voyage from Teignmouth to Cork I was all right in the English Channel, but when we opened out the Irish sea and we had to face a strong north-west wind, which was a head wind, and the vessel was pitching and jumping all the time, I stuck it as long as I could, but I was a couple of days eating nothing.

I remember the first day after passing the Longships, (that's off Land's End), the head lashing on the mainsail that keeps the mainsail to the gaff - that parted, and the A.B. had to take a length of line (perhaps a couple of fathoms) go aloft, go out over the peak halyers, he secured the head of the sail, that I was so worried about that man being up there, the gaff swinging you know, that I forgot the seasickness till he came down. But after he came down in safety, I was sick again.

Well now, we went on and I seemed to be getting very weak, and father (in one of his soft moments), he must have thought about it before, because he didn't take drink at sea at all, but this time a bottle of brandy was produced, and he gave me some tots of brandy, supposed to settle me down a bit, and as fast as t'would go down t'would come up again, and then I'd get something said to me for wasting good spirits. He said he could have drunk it himself you see, but he kept it for me. He thought I needed it best, or most.

Well, in due course a couple of days after, the wind backed away south-west, and we got across towards the Daunts lightship outside of Cork harbour, and I was called up 'cos I'd been asleep a good bit of the time (called up to look at the Irish coast), and do you know, I felt hungry, and the cupboard door was never shut, as far as I was concerned. I went below, and I got hold of some sea biscuits and bread & butter, and I had a meal before I got in harbour, so that when I got to Cork of course it was all forgotten very quickly.

INTERVIEWER:

Did you get over this sea sickness?

CAPTAIN SLADE:

Never in my life, but I got that I didn't take any notice of it at all. I'd be sick then get over it, and eat something, eat something dry, and then that was something to bring up, but it didn't hurt me at all.

INTERVIEWER:

You mentioned just now 'sea biscuits', what other food... what was the sort of standard food you were carrying?

CAPTAIN SLADE:

Well, we used to carry the salt beef you know, and beef for salting in, in the harness cask. We had some salty fish.

Now for breakfast, it was mostly margarine instead of butter, but for breakfast we'd have one morning a couple of slices of bacon, no egg like they have today, and the next morning there'd be a change (this is for breakfast mind you), it would be salt cod. The bit of fat that was saved over from the bacon would go on the salt cod to make it more tasty. The next day it would be Quakers oats that was... and then it would out and round again back to the bacon.

Now for dinner, if we were in harbour, we might get a bit of fresh beef. But if there was a lot of meat accumulated in the harness cask, it was salt beef, potatoes and vegetables all boiled together in the one pot, but we thoroughly enjoyed it. There were no afters at all, you just simply had to make a meal of that or go without.

INTERVIEWER:

And then was there a late tea or supper?

CAPTAIN SLADE:

At sea we'd have our tea at five o'clock. That consisted of the remains of the bit of beef that was cooked, sometimes the boy had the bone to pick. But of course, it went round to all the rest first you see, and in harbour we'd have our tea: that consisted of a bit of meat to pick and bread and margarine, or maybe a bit of bread and jam (we didn't have the both together).

After that the boy had to clear away the mess as usual, then he had to get his galley store ready for the next day, clear out the fire (with no supper), the fire had to be cleaned out, the galley had to be cleaned out, the breakfast had to be got ready for the next morning, and then after he'd done that he had to skin the potatoes for the next day, for dinner, get everything ready overnight. By the time the boy finished, 'twas time to have a wash and go to bed.

INTERVIEWER:

He certainly seems to have had a fairly busy life. What was he paid for all this work?

CAPTAIN SLADE:

In the Bristol Channel vessels, just down as far as home, they'd give the boy about six bob a voyage, that wasn't very much, then he'd get to half wages. (26 shillings a voyage, was the man's wage, and the food in addition of course), and the boy would get half of it and he gradually got on to three parts until he got to man's wages. As far as I was concerned we used to do about 20 cargoes a year, and I was allowed one shilling per cargo - 20 shillings a year.

INTERVIEWER:

And your father pocketed the rest?

CAPTAIN SLADE:

Well, it was only typical of Appledore boys in those days where their people owned the vessels and they had to sail on them to make them pay. I wasn't the only one, there were others like me, you see 'twas a sort of family affair. Say a man bought a little vessel, he'd take his son: his family with him. The cheaper the crew the more they put away for their old age.

In those days there was no welfare state, and if you didn't work for your parents when you were young, you had to keep 'em when they got old. What was the difference?

INTERVIEWER:

But, it's almost difficult to understand Captain, with all this tremendous amount of work going on, how you managed to learn anything theoretical about the sea - about navigation.

CAPTAIN SLADE:

Well, of course I was very seasick, as I've told you, and my father seemed to weigh things up. First of all, when I was in Cork he gave me the compass to draw. Well I drew the compass and he was so pleased with it he said: “That one's good enough to go on a card". I did it all, stayed one evening and did it while they were ashore you know.

Then he started to teach me how to handle the tide table, books of directions and things like that. I was still 12 years old you know. Then I got to 13 (perhaps something like 13 or 14), and I had the free run of all the charts - everything. He never grudged me anything like that, I could go and take it when I wanted it, and study it, and I did study it.

Then it got, in the end, he'd see me being a little bit green (seasick you know), and he'd say: "Go down and tell me how far off the vessel is and reckon her up” - dead reckoning - where she's got, perhaps we'd be beating to windward across the Irish sea, and of course if there was a head-wind, 'twas a case of zig-zagging, you know, and I'd have to reckon up every tack, allow for state of tides and things like that. He'd taught it all to me, and I had to do that. When I was seasick he thought t'would take my mind off you see. But 'twas no use afterwards for me to say I couldn't do that, I didn't feel like it, you'd got to do it. That's what it amounted to.

INTERVIEWER:

At what age did you first really navigate a ship though?

CAPTAIN SLADE:

Well, I remember going round Cape Clear bound up to a place called Kilorglin – it's close to the lakes of Killarney, with a cargo of salt. We had to get into Dingle, it's at the head of Dingle Bay. We had to get into Dingle and 'twas dark, and there was a heavy gale pulling the vessel, and he was afraid to leave the wheel. The mate was there in attendance, and he turned round to me, and he said: “Now come on, I want you to take her into Dingle tonight. You give me the course over from Valencia Island you know, and then get me on the right course to get me into Dingle and look at the little sheet that's there and tell me where the shallow water is".

Well I did, I felt I could of course, went over the course and opened out the light in the entrance to Dingle harbour, and got it on a bearing you know, and then I come up, I said: “Father, you must keep about 100 yards off that light, and go close along the rocks, ignore the other side, and then you'll open out Dingle piers, and you can anchor there anywhere.”

We did, - went in and didn't touch anywhere, but of course there was no praise you know.

INTERVIEWER:

But how old were you then?

CAPTAIN SLADE:

I reckon I was about 14 then.

= = = = = = = = = =

Programme no. 2

= = = = = = = = = =

INTRODUCTION:

In any business, the relations between a father and his son can lead to complications, and sometimes to a complete break in their relationship. When that business was sea business, and when the father as Captain worked himself and his son to the limits of endurance, that break was never very far away.

In 1904 at the age of twelve William Slade first signed on under his father's command as a ship's boy, for the magnificent sum of a shilling a voyage; and there's no doubt his father drove him hard, harder perhaps than he would have driven a boy who was not eventually to succeed him in command. Nevertheless, under the apparent harshness, there did exist affection, and what is more - confidence. Young Slade soon replaced the deck-hand, then the able seaman, and at the age of 17, five years after he first went to sea, the father promoted his son to be mate. You might think, as I did, that that promotion would lead to some easement of the son's burdens.

CAPTAIN SLADE:

I think it became harder, because we were always short-handed, in the ELIZABETH JANE - she was 170 tons, much bigger than the other one, but still came back to the three hands, and instead of being clear of the cooking, I had to do that as an extra duty to being mate.

INTERVIEWER:

Was there a particular voyage of that ship that was a very difficult one?

CAPTAIN SLADE:

Well, we'd had the vessel for a considerable time, when we loaded a cargo of coal for Porthallow - that's a beach inside the Manacles, an open beach. That place of course was only fit for little 70-ton vessels, but father again was after the money, and he got extra freight for going there.

He'd got into an argument with another skipper, of a ship called the SUZANNA, and he was told that the ELIZABETH JANE wouldn't sail. Since he'd got in over the bar, well that touched father's pride. So when we toured down to Newferry, we toured right in on the ground, that night we had to clean her bottom with anchor lamps.

We shifted off afloat after cleaning her bottom, and then it was a question... we all sailed, there's a lot of ships sailed from Newferry at the time, but among them - the SUZANNA, and father was just tilled for a bad time, he didn't mind what was going to happen, he was going to beat the SUZANNA.

So, we worked down the St. George's Channel, sometimes double reef sail, sometimes single reefed, having a hard passage. Each time being mate I had one watch alone, (there was two in the other watch - father and the A.B. you see) I had one watch to myself. In addition to that, (of course, I can remember it vividly), it seemed that when it was my turn to go below, at twelve o'clock in the night we'll say, there was always: "Oh, we'll set the sails" or: "We'll set up some sail, or give her more canvas", because there'll be two on deck you see. That meant that I was losing an hour of my watch. Then before it come to the next watch, I was called half an hour or so before time to take in the sail again, that I was losing part of my watch all the time. It seemed to me that I got no rest at all. There was no sleep - by the time I'd get to sleep, I'd be up again. But of course, being young I had to do it, there was no use grumbling about it.

Finally we got down to Trevose, and the SUZANNA was the only vessel left in our company - all the rest had gone windbound, and I can see my father now, looking over the quarter watching the SUZANNA, both of us double reefed, and then he said: “Give her certain sails" and we started to put the sails on her until her lead dead eyes was underwater, and he stood to the wheel, grinding his teeth, and we just marched away from the SUZANNA for all she was worth.

The next day we went round the Longships. When we got round the Longships 'twas blowing hard again southerly, and again in my watch (the middle watch that night again) the vessel's reefed right down, and a squall fell into her, and I said, (I shouted to father): "You'd better come up and stand by - it's pretty hard here".

He put his head out of the cabin companion way, and he had a look around in the black darkness. He said: “Keep 'er goin' and call me when the watch is up" (just shouted it at me).

I thought afterwards: 'well she can keep goin' now - if anything happened I wouldn't call you!', and I didn't call him.

We weathered up the Lizard and come daylight, wind was still southerly, he had a look at the sky, and a look at the weather generally, a southerly wind was right in on that beach. He said: “It's nearly high water, I'm gonna stick her right in."

And in she went, and she freed up two or three feet of water, everything on 'er, right in on the steep beach. He said: “The wind'll western through the day", and it did! He'd got an uncanny way of seeming to foretell things.

INTERVIEWER:

Must have been a superb seaman really.

CAPTAIN SLADE:

He was. There's no doubt about it, he was. But he went ashore to see the merchant, and the next thing I knew, water was ebbing away, we'd got the gear up, and we started to work cargo. You see on a steep beach, the carts was under the bow, we could swing it in there. We worked cargo 'cos Father, he went into his bunk and had a bit of rest - he didn't work the cargo.

Then we worked until the water was up under the axles of the cart on the flood, and then I had a wash and a bit of something to eat, the other chap turned in to sleep. I'd no sooner got turned in before it was: "Billy, jump up here, I want to heave the vessel in a bit further." And that sort of things went on day and night, I hadn't got any sleep - I was worn out.

On the Saturday morning, about 4 o'clock, we'd finished the cargo and un-moored, and going to sail into Falmouth. When we had our breakfast in there, the order was: "Get the vessel cleaned up for Sunday, wash down the decks and wash the paintwork round." I was just worn out.

When Father went (I was a bit afraid of him you know) I said to the A.B: "Keep a look out" (he went to shore in somebody else's boat you see to buy something for the next day’s dinner), "Keep a look out and let me know if you see him coming - I'm bound to lay down, I can't go it any longer." The decks seemed to be coming up to meet me all the time. I just managed to throw a bucket of water over, to knock the thick of it off, and I got down (boots and all on) and got in on top of me bed and I went to sleep - I knew nothing more about it.

But instead of the other chap keeping watch for father and telling me when he was coming, he went to sleep. Father came aboard and caught us both sleeping. The next thing I knew he was in my bunk pulling me out of bed: "What do you mean by sleeping in the middle of the day?" I can remember standing on my legs (or trying to) with the tears running down my cheeks. And he said: “What's the matter?" and I said: “I don't know".

But I just simply... the tears was running, that's all I know about it. I couldn't answer. He just took another look at me and he picked me up in his arms and laid me in the bed and said: "Stay there as long as you like" - I didn't wake up till the next day.

INTERVIEWER:

Although your father was so hard with you, there seems to be underlying current of affection from him to you...

CAPTAIN SLADE:

It was there, I knew it was there, but I've got a job to bring it out. I've seen it. Lots of times when I've been in difficulties.

INTERVIEWER:

Did you feel you wanted to bring out his affection, I mean were you fond of him?

CAPTAIN SLADE:

I was of course, but I never tried. But there were times... I'll give you an instance...

I was running in Newport river blowing hard, and the whole mainsail was on the vessel, and it ought not to have been on her, she ought to have been reefed. But being so close to our journeys end, (Newport river) he wouldn't reef. We were going up round a certain point when the main boom came over suddenly in a puff of wind.

Now the boom was 40 feet long, and about nine or ten inches thick. When the boom came over sudden like that, I knew that something was bound to go. So I was as quick as lightning gathering half the sheet through the blocks, gathering like this as it was coming. That would ease it out. Nobody told me to do it, but when the sheet went out I'd forgotten where the bites of the rope was going, and my leg got in a bite and I went right up in the bullseye leg first.

INTERVIEWER:

Jammed into the block.

CAPTAIN SLADE:

Yes, and I let out a yell you know. I'd got a leather sea boot on, and the first words was: “Oh! my poor boy, are you alright?" (There was the note of affection you see).

I said: “Yes, I'm alright father."

Then: "You so-and-so, what did you put your leg in there for?" - that was on the same breath! Momentarily, it was there you see: "my poor boy - are you all right?"

Well, I got on my legs, and he went to look after the sails - I was put to the wheel to do as I was told, as I was on one leg.

When we got in the dock, the police doctor came aboard (as t'was in the night you know), and he said: "there's no bones broken", but the leg was in bad condition, the boot had to be cut off, (I thought I was in for a holiday) but not on your life! We were only three handed, but he said..."If you can't do any work - you can look after the hatchway and discharging". I'm supposed to go down slinging timber, but I couldn't do that - he knew that, so he put a man to sling the timber, but I had to do the deck work.

Well we left there, I thought I might go home and have a holiday, but not likely. Left there still three handed - me with one leg, all the way across to Ireland, after that we're bound to a place called Clonakilty. I was taking my four hours wheel, on one leg, and the other one - the knee stood on a box to keep my weight, and I took my four hours wheel each time.

When we got across the other side, we couldn't pick it up, t’was dirty weather, and we were off the Daunts lightship somewhere, but afraid to run further because the Irish land is always capped, and you're on it before you see it. So we hove her to.

We had to take the lower topsail (that's one of the sails aloft), and I had to go aloft on one leg - on one knee and one foot - up over the rigging to the mast-head and out on the yard-arm to take in my share of the topsail - he didn't say: "I'll do it", or anything like that. "Do it!" - that's all there was to it, didn't take any notice of it.

When we got to Clonakilty eventually, he said: "Well if you can't run the plank" (you see the mate used to run the basket ashore - run back and fore the plank), "If you can't run the plank - you can heed the winch.”

So I had to heed the winch - the hand winch - with one leg again on the box. That was my holiday!

INTERVIEWER:

Captain Slade, when you reached the rank of mate, had your sea sickness got better by that time?

CAPTAIN SLADE:

I should say it had subsided to an extent, but I was subject to bouts of it all the time. I may go perhaps one voyage and not have it, and then the next voyage it would come back as bad as ever. I could never depend on it at all.

INTERVIEWER:

What was the effect of the sea sickness on your father, 'cos he wasn't seasick was he?

CAPTAIN SLADE:

Oh, he was never seasick in his life, he had no sympathy for me. It annoyed him to see me seasick, especially when I was mate you know.

On a voyage from Courtmacsherry to Totnes, we'd been to sea for perhaps 24 hours or maybe more, maybe 30 hours, with a head wind, zig-zagging around from the Irish coast across to the Scillies you know, and I was bad that voyage. He said to me one morning: "Go down and reckon the vessel up, tell me what course to steer to the Sevenstones" (the wind had veered you know, to the westward).

I had to do it, and it was alright, I could get on alright, go down and do what I was told to do, the navigational part, and I gave him the course to the Sevenstone lightship, and he didn't question it at all – just carried on.

Eventually we picked up the Sevenstone lightship, and… 'twas on a Sunday, we hadn't been able to buy any meat, and we'd got short of meat, there was no butchers shop in this little place Courtmacsherry.

We always carried a stock of bully beef - 2lb tins. So he said: "You make a pie out of a tin of beef, put all the vegetables in it, and make a crust to go on it, (he said) that'll be alright."

Now, there was a nasty sea and a strong wind, and our galley (the cooking galley and cooking stove) was right aft, behind the wheel in a house there, and I put it on the stove after I put it together and went down to clean the mess up preparatory to taking the wheel again.

While I was in the cabin, suddenly I felt her go head over heels into a heavy sea, and I jumped up on deck (because I heard a big rumpus you know). When I got on deck, she'd shifted the galley stove, the pie was running along the lee scuppers where she'd put her quarter under, and father had put the bucket on the wheel, and he's chasing the pie with the pot in one hand, and looking for the pie with the other hand, and scooping it all in the pot together - all the lot together - dough and all, and shouting: "I shall lose my dinner!".

He was hard you know, he didn't mind what he ate, but when I saw him scooping that lot in, I was already weak in the stomach, up come my breakfast. I was down over the lee rail, and t’was all coming up out over this, I couldn't stand the look of it at all. He turned round and he said: "After all these years you aren't worth 30 bob a month", and he went for me hammer and tongs, because I was sick and bad and well, something passed between us, I lost my head and I retaliated. I'd had about as much as I could stand, and when he saw the condition I'd put myself in over it (because I was annoyed as well as he was to think I was so sick), but he'd done it, turning my stomach - I'd got a weak stomach you see. He came back and he put his arm round my shoulder, he said: "Never mind, you'll make a man yet!"

INTERVIEWER:

It's quite obvious captain, that all this time your father was training you to eventually take his place. When did that happen?

CAPTAIN SLADE:

That's quite right, he was continually giving me the works to try and get me to take charge. Sometime after the last episode of the sea sickness, we got to Ilfracombe with a cargo of stones, and to my great surprise, one day he said to me: "I'm retiring".

“Well (I said), who's going to take charge?”

He said: "You are".

“Me (I said), 'tis only a little while ago you told me I wasn't worth 30 bob a month, and now you're telling me I've got to take charge.”

He flew off the handle immediately. He said: “What have I been driving into you all these years?". He said: "You've got to take charge, and I'll lose the vessel rather than you should fail. I don't care what happens, you've got to take charge of the vessel".

Well, I had to obey again.

INTERVIEWER:

All these years Captain, would it wasn't so many, how old were you when you...

CAPTAIN SLADE:

From 12 to 19. Seven years he'd been drilling me all the time.

INTERVIEWER:

And at the age of 19 he put you in charge?

CAPTAIN SLADE:

My birthday was in April 28th, and I took charge in September 1911, that was 19 and 6 months we'll say.

INTERVIEWER:

And then I suppose your father went back to live at Appledore?

CAPTAIN SLADE:

He lived at Appledore, he was still there you see, there's no distance from Ilfracombe to Appledore. We were both home and I was sent to Ilfracombe to take charge of the vessel.

INTERVIEWER:

And Appledore in those days...

CAPTAIN SLADE:

It was a hive of industry. There was crowds of little sailing vessels from the quay right up and down so far as you could see. There was a forest. These vessels kept the shipyards going for one thing. All the men that worked in the yards depended on the ships for their living, the repairs, the money they earned went round the shops, came into Bideford, Appledore kept Bideford going in those days, and Bideford didn't like it very much. They were jealous you know. But, to come back to the thriving place...

INTERVIEWER:

They all used to come home for the big holidays, for Christmas...

CAPTAIN SLADE:

They come home for Christmas yes, always, they try to get home. But of course there's always some left away, but they'd congregate there until there wasn't a berth left, just fill up as far as you could see up the river, and down as far as the Seagate Hotel. Then when they had to go over the bar together, they have to watch a tide you know, they'd all get under way, and I've seen them going down the river towards the bar pushing each other clear with paddles and oars and boathooks, whereas to avoid collision.

INTERVIEWER:

I suppose there were any number of old retired Captains ashore to watch and criticise all these manoeuvres?

CAPTAIN SLADE:

Oh, you'd get criticism all right, they used to stand on the quays and on the hills you know, and say what ought to be done, just the same as the footballers do at a football match - the best referees are always on the line - just the same with the sailing vessels, you'd be criticised no matter what you did!

INTERVIEWER:

But I suppose you listened to their yarns of the days of the big racing did you?

CAPTAIN SLADE:

Oh, when I was a youngster, my father's vessel the ALPHA was one of the fastest. There were four or five very fast vessels - we'd got two or three of them.

The two outstanding ones in addition to ours were really North Sea trawlers converted, they were iron crafts, one was called the BENITO, the other the LEADER, and I remember one time when there'd been a few challenges going round - the LEADER and the ALPHA went over the bar together. Well, going down through Appledore pool, all the men were on the quay watching them, you know, to see which was gaining a little bit. The ALPHA was a little bit ahead of the LEADER, but not very much.

I was a youngster of course - a schoolboy at that time - and my favourite naturally was my father’s ship, the ALPHA, and there were the men arguing, and I was among the men with my mouth wide open, you know, and at last an old chap called Guard - Sam Guard, he said: "The ALPHA's going two foot to the LEADER's one", and I felt a terrific thrill to think my father's vessel was going two foot to the other one, but you know 'twas an exaggeration, there's nothing like it at all, there was very little difference, if any, but that was their way of exaggerating the race.

They got over the bar, up around the corner, out of sight, and the local curate was very interested in this racing, you know, he cycled the 25 miles from Appledore to Ilfracombe to see which passed up first. Later on we received a telegram from the curate: "ALPHA and LEADER passing Ilfracombe – ALPHA leading". Well, of course I was thrilled again naturally.

Well, I can only carry on that race with what I've heard - the account of it. Going up under the southern shore, the LEADER set what they call a balloon foresail - 'tis a spinnaker on the fore stay, you'd understand that if you've seen yachts - well that gave her a little benefit, but still the ALPHA kept slightly ahead, not gaining anything. When they got further up above Lynmouth, the wind shifted a bit. That allowed the ALPHA to set her squaresail. Again, the ALPHA had the privilege, and she went away from her opponent, and she arrived first on turn for discharging.

INTERVIEWER:

Of course, racing wasn't pointless, it was a question of getting to a discharging point...

CAPTAIN SLADE:

They had to get to the first – there was a point arranged, the one with the anchor down off the berth, was the first in turn for discharging.

INTERVIEWER:

And that meant you could eventually get an extra voyage, she'd make more money would she?

CAPTAIN SLADE:

If there were a lot of vessels going away from Appledore, always the first one was one of those five: the ALPHA, HEATHER BELL, ULELIA, LEADER and BONITO. 'Twas always one of those that was first.

INTERVIEWER:

You talk rather Captain, of the happy days, there must have been many days of anxiety in Appledore when there were heavy gales, and the fleet - the ships were out.

CAPTAIN SLADE:

Yes, I remember one episode when I was young, we'd got caught down in Bude bay, with a light vessel, and she was driving into the rocks all the time, no wind. The sky was looking very dirty, very bad, I didn't understand the danger, I was too young to understand it, and suddenly I heard father shout: "There's wind coming". He could hear it, and sails were let down as fast as possible, you know, but when it struck her 'twas right on the beam, and she was right on a lee shore, close to the rocks, and she went right over on her bulwarks.

Well, I jumped up out of the cabin, I was down there singing hymns to be truthful, to myself you know, I wasn't seasick then that voyage. I jumped up on deck, I'd got a pair of father's shoes on, and father put his arm round my shoulder, because the vessel was close to the rocks, and there was the expression again - soft expression. He put his arm round me, he said: "My boy, you'll never see your mother again" – you see she was in danger of driving on the rocks there, light like that.

Then he just pushed me away and he started to shout, giving orders to the crew, and again there was the manliness of him you know, 'twas through his teeth - he'd got to do it, and the mate came running back over the deck: "Will she do it Captain, will she?"

"Do as I tell you, instantly.”

And so we started to set the sails, her bulwarks was in the water, but he still set sail on her, and I was down the lee side and they were pulling up the mizzen, and I was holding on under the pin taking in the slack - a little boy - and I was up to my waist in water, so you know what she was like.

Well we got part/some of the rolls (or reefs) out of the mizzen and set some of the head canvas, I didn't understand then what was happening, I only know that he was driving her unmercifully. Well now, there's a reef of rocks runs off Hartland Point called the Tings; they run north quite a distance. Father, he knew she wouldn't come round on the other tack, and it was a question of whether he knocked those rocks or not. I've heard him say that his heart was up in his mouth, he knew he was close, but how close – would she weather or not?

Then she seemed to get off, and he explained it to me after, 'twas the ebb tide coming out of Bideford Bay dragging her to windward, and that's why she weathered up the point, but she was flat on her bulwarks all the way. It was really an anxious time.

INTERVIEWER:

And if you'd hit the rocks that day you wouldn't have been here now Captain.

CAPTAIN SLADE:

No, shouldn't have been here.

INTERVIEWER:

Captain, did your father really retire or did he become a backseat driver of your ship?

CAPTAIN SLADE:

He was always ready to criticise and there was no rest. I had letters always finding fault, there was always something wrong. If I was laying in harbour, 150 or 200 miles away, the weather had to be just the same as he had it. He probably had different weather from me altogether and he'd wonder why I couldn't get out to sea. I'd get a long letter, criticising me for staying there.

I nearly lost my vessel once in the entrance of Cork harbour because I had a letter, asking me what I was laying in Cork harbour for. I tried to get out. In going out she missed days, and I had to wear her. You wouldn't understand that perhaps, but that was turning the vessel round the opposite way, and she nearly went ashore, but I got out. It was all through father's letter driving me you see, finding fault because I was laying there, and I knew it wasn't right to try.

I remember one particular voyage, I'd taken my cargo of washing soda to Exeter, and going up the river Weaver, to Northwich, they'd given me the wrong heights of the bridges and I knocked the tops of the two top masts off. That was my fault, but he got paid for it because they'd given me the wrong heights to the river, you see - the bridges. Well I got a long letter about that, all what I had done and what I hadn't done was nobody's business, but it was all my fault in any case. I got fed up with it.

We left Liverpool and we got a crowd of schooners, you know we didn't bother to send the yards up again, just went under fore and afters. Got down as far as Holyhead, they all went windbound. I was headstrong - mad if you like, but I just put the vessel under double reef sails and went across towards the Irish coast, to look for a north west wind.

While I was under the very small canvas there was a heavy squall, and we were reported, (the Holyhead kingstern boat reported seeing a fore and aft schooner disappear in the waves). Well of course they were going at such a speed, I suppose in the squall they did miss us. There was an Appledore ship in Holyhead, he brought home the news and it soon spread about, that father was in a terrible state.

I think that it was about 10 days after that, that we arrived to Exeter and we'd gone through a heavy gale of wind, and when we got there the cargo was damaged (part of it), through being in this gale you see.

I got a long letter then, telling me I ought not to have been to sea in weather like that, I ought to have known better, and there was a lot of criticism, so I was just about fed up with all of it, so I wrote to him and told him that the best thing he could do was come and take charge of her himself, that I'd rather go deep water out of it - I wanted to go deep water.

Then father appeared on the scene, and he said to me: "What did you write me a letter like that for?"

I said: “I meant every word I said father, I've had enough, and I'm not having any more. It seems to me that I'm not capable, according to your letters, therefore you take her, I've finished!"

"Come down in the cabin (he said), I want to talk to you."

Well he talked me over, and in the end I said alright. He said: “Now go home and have a few days with your mother".

That's how that lot ended.

INTERVIEWER:

Did he ever find anything else but fault?

CAPTAIN SLADE:

Yes. I remember once leaving Bideford, bound to Glasgow with a cargo of clay. When we got opened out the bay, we had a strong south-west wind, and we drove her as hard as she'd go for the Milford islands.

That evening in the dark, we found our way up through Milford islands, (it wasn't much trouble, after we'd picked up certain marks), when we'd got above the South Bishops (that's on the Welsh coast), we set the squares along the vessel reefed.

We'd taken down all the other square canvas and rigged her as a fore and aft schooner. And I said: "She's got to carry the squares on the out to make up for the topsails being gone."

Well I didn't take any account of time, but in due course I arrived to Glasgow, and I was discharging the cargo in Glasgow and a letter was passed aboard, (I'd already sent a telegram home, you know) "Do you know that you've made a record passage? You're discharging your cargo in Glasgow and it isn't 60 hours ago you left Bideford!"

And when I read it I thought to myself: "Well I'm bothered! - at last - fathers satisfied", and that seemed to me something of a miracle!

= = = = = = = = = =

Programme no. 3

= = = = = = = = = =

INTRODUCTION:

From a nautical point of view, perhaps the most obvious after effect of the first world war, was the virtual disappearance of the commercial sailing ship. I can well remember that till 1914 you couldn't make a passage from Gibraltar home without sighting some of the magnificent deep sea sailing ships, and on reaching the chops of the channel the coastal routes were alive with small schooners, ketches, and sailing barges.

The change from sails to steam and motor, though still resisted here and there, could no longer be still. Appledore as you'll hear, held out as long as any place, and the ships of Captain William Slade were certainly not the first, even at that port to install diesel motors.

The younger men of Appledore, and the other small ports had been among the first of the navy's reservists to be called up, and an invaluable core of skilled seamen they proved to be. I had thought that it was the shortage after the '14 war of young men experienced in sail that was partly responsible for the change to motors, but Captain Slade explains it differently.

CAPTAIN SLADE:

We could get crews after the war, but it was more a question of being able to make voyages, and the economy I think. We could do away with some of the sails; for instance, make them last longer, and we could make more voyages with the motors.

INTERVIEWER:

I heard you were a bit slow in Appledore getting over to motors, other ports beat you to it didn't they?

CAPTAIN SLADE:

Much too slow. The Braunton men had motors years before we did, they had them I should say in 1909 or 1910, if not before. But our family believed in the sail.

INTERVIEWER:

And you rather looked down your noses at them?

CAPTAIN SLADE:

Well I don't know, we didn't bother with them, that's all. I was doing very well under sail and quite happy. When I got in harbour I could put my collar and tie on and go ashore, but after the motors were put in I was nothing but a filthy mess from Monday morning till Saturday night. I met the voyage at sea – if anything went wrong with the motor I had to go down and put it right, find out what was wrong and put it right, or often run a bearing out. Had to fit a new one at sea, and in harbour I had to go down where I should be ashore enjoying myself, start working about the engine, cleaning it up, repairing little things, perhaps little small bushes required, I had to make a bush and put it in on a pin to stop the wear.

INTERVIEWER:

Fitting these motors, did it mean altering your accommodation?

CAPTAIN SLADE:

Oh, it did away with the accommodation on the first ones. The bigger vessels like the M A JAMES had room because they had a mess room foreside the cabin, where the crew used to eat their food. That mess room became the engine room. But with the MILLOM CASTLE and the HALDON and one or two others of our vessels, half the cabin had to be taken and really the accommodation was miserable, and the smell of the oil was everywhere. That made me worse when... I was seasick over that very often.

INTERVIEWER:

So really it was a very sad day for you when you went over to motors.

CAPTAIN SLADE:

I'd much rather have had the sailing vessel. But we had to come up with the times and we had to compete with others. So there was no question about it, we had to go into the motors.

INTERVIEWER:

And freights were falling at that time, weren't they?

CAPTAIN SLADE:

Yes, they were falling, and after the war you know, but still I had a very good time for the first 12 months, I picked up a lot of money, mostly in the French trade.

INTERVIEWER:

Captain, those old engines, did they give you a lot of trouble… breaking down?

CAPTAIN SLADE:

Occasionally, they did give trouble, but one particular voyage that I remember they gave me a lot of trouble. I was off Swansea and we had a double cylinder engine, and one part of the engine (half of it) smashed up. Well, my mate wanted me to go home for repairs, but I'd been used to being under sail for so many years that I made up my mind that I'd sail the passage.

We got across to the Irish coast under sail and the weather was looking very dirty and very bad, and my brain was on how to make this engine work all the time.

Finally one morning I made up my mind that I'd try it on one cylinder. So I unbuilt the after cylinder, turned the piston upside down, hung it with the tackles and beams to cover the exhaust ports. I put a piece of wood in to plug it from the inspection plate and fastened it tight against the exhaust ports, then held up the pumps and plugged all the water courses (lubricating oil) and just put it on one cylinder, with all the after cylinder in pieces. I thought to myself then: "Well I'll try it,"

So I started the engine up and sure enough it went on the one cylinder alright, but when we put it in gear, the one cylinder wouldn't take the propeller.

Still I wasn't beaten, I said: "I'll try again," and I got one of the men standing by the lever to put it in gear. Started up the engine again, and I said: “When I tell you to put her in gear, you do it." And I started to give her oil just as much as she'd bear - there was a water injection, a fuel injection as well to keep the bulb cool. When I was ready, I shouted to him to put her in gear and she did keep on, she kept on turning, and then I adjusted it to take the propeller on the one cylinder, and when it got hot I added the water then there was vapour, vapour and steam in the cylinder head which gave it power. It went all the way without any trouble at all, about 40 miles until we arrived in Cork harbour.

When I got in Cork harbour I stopped the engines - this was about two o'clock in the morning - and I had to go up the river to Ballymakeera the next morning, the engine refused to start!

Well we sailed up. I couldn't rest that night. What was wrong with the engine? If it went once it should go now. I laid awake, although I'd had nearly all night out, I laid awake worrying about it.

At one o'clock in the morning I got up out from my bed, the tide was in, and the solution came to me. I put the engine back where it started from, reduced the fuel and things like that, and away went the engine – alright. I knew what was the matter you see. The wheel couldn't turn over because there was too much vapour going in, there was too much pressure there. So easing the pressure on the cylinder head it would turn alright, then I had to give it to 'n gradually you see. In that way I motored from Cork harbour back home, with one cylinder. That was a distance of about 150 miles.

When I got in over the bar, my father said to me: "Well what have you come in for, your engines alright?"

When he looked down the engine room he had a shock because half of it was in pieces, out on the engine room floor. He said: "I don't see you want two cylinders, one cylinder doesn't burn as much fuel as two, why can't you go away like you are, you'll save money and fuel and you'll carry on just as good as you did before."

But of course I couldn't see that at all, I wanted the two cylinders!

INTERVIEWER:

You managed to work the old man round did you?

CAPTAIN SLADE:

Oh yes, he had to go my way.

INTERVIEWER:

One other thing Captain. When you first began putting these engines into the wooden ships, didn't they play 'old harry' with the compasses?

CAPTAIN SLADE:

Well of course, but my father was a very stubborn man, he'd been used to the sailing vessels, and he wouldn't have it to be that because the engine was more than two feet away from the compass he said that it would be quite alright, and I had to toe the line up to a point.

He took her out into the river and he put her head towards a certain spot, and he said: "You're alright on this course" (it was a southerly course).

"Yes, (I said) but every time you swing the vessel there's so much deviation that's got to be allowed, and we've got to have a deviation card to add the amount necessary. It's different on every point", but he wouldn't listen. In the end I had to go away without the compass being adjusted.

Well, we got to Ireland alright one voyage (I don't know how) but there's a head wind and we had to zig-zag but it didn't matter much, I knew every part of the Irish coast. I'd been used to it and I knew when I sighted a piece of land I knew it, wherever it was. But we got down alright, and we came back to Gloucester, with a cargo of oats.

Well we got up to Kingroad (that's Portishead,) there was a good bit of traffic there and I'd been up the Severn hundreds of times and I said to the mate: "Well I've got an engine, and I'll go cross, and dodge about in the Oars" (that's part way up the Severn.) Didn't think of anything happening at all – forgot the compass was out and it was dark. So I steered the usual course north-northeast, from what was called the Cockburn buoy.

When I got so far across, I couldn't pick up the leading lights, so I made up my mind I'd turn round and wait until the tide had flowed up a bit. So I'd only just turned round, there was a flat calm, when the engine stopped. I was new to it. I didn't understand much about it, but I went down below and I was there swinging the wheel and trying to get it to go. Of course the tide runs are fast there in the Severn, and I was afraid to let go of the anchor just below the Shutes and the next thing I knew, she struck aft, on a rock called Groggy. She took the whole keel out of her from end to end and broke the stern post. She dropped into deep water and the engine went.

I didn't know then what was the matter with it, but we motored to Sharpness and went on to Gloucester. Put her in dry dock in Gloucester and found the keel gone.

Well father came away and I said: "Why not condemn it and let me get out of it?" I was tired of it.

He said: “I'm not going to do that, I'm going to repair the vessel."

It eventually cost £500 which was a lot of money in those days, but father said I'll stay here and make a few voyages with it. Down to Briton Ferry the price was fairly good down there, and we agreed to just pay ourselves a living wage and let the balance go towards the repairs. This meant that of course that I was losing a good bit but that didn't matter, I didn't mind a bit.

Well one voyage we got down to the Scare-weather lightship and it was thick weather, we couldn't see very far, and I thought to myself: "I'm going in here on much the same course towards Briton Ferry bar as we should go in over the Shutes." So I said: "Father you take the wheel and steer her in, and I'll go down and wipe the engine down and clean it up a bit."

I went down there and I was listening, knowing what was going to happen.

He took her in alright but he'd missed the Mumble head into the fog. The next thing I was waiting for (t'was dead smooth water, I knew she wouldn't hurt), The next thing... "Billy you've put the vessel ashore" (I hadn't been on deck).

Well, I jumped up and I saw a buoy way up above us. I didn't say anything. He backed her off, the ground was dead low water you know, and he stuck her in the second time. I thought t'as has got far enough, so I said: “Look here father". Don't you understand, the compass is out on this course. I've told you before, you won't listen to me, but the compass has brought you down here and you're down in Swansea bay on the sand."

Well he mumbled and grumbled a bit (you know) about it and the vessel was backed off, and away we went up to Briton Ferry bar after without any trouble, but he still wasn't convinced.

Well we got back on the way up for another cargo of barbed wire stuff to Gloucester. When we got the Cockburn Buoy, where we started from when I knocked the keel out, again I played the old trick. 'Course she was empty; I knew she'd have water over Groggy when we were empty, but I was loaded when I went on it. I said: “Father, I want to go down and wipe the engine down a bit and I've got a good bit to do down there, you take the wheel” (I didn't give him any course). He steered over from the Cockburn buoy the usual course (north-northeast), and at last he started to shout: "Billy come up here, I can't make out these lights, so I can't see the leading lights."

I went on deck just chuckling to myself. I thought to myself: ‘Now I'll persuade him,’ So I said: “Oh, you can't find the lights father?" He said: “No."

I said: "Neither could I when I came over that course. Now, (I said) I'll tell you what to do. You're too far to the westward. Turn the vessel round and steer away to the eastward, and you'll open out the leading lights. They're mixed up in Chepstow river shipyard lights."

He did what I told him, and after that he kept quieter, he knew why I'd knocked the keel out, but that finished the grumbling all the time, and he was satisfied that I wasn't to blame.

INTERVIEWER:

Then he had the...

CAPTAIN SLADE:

I had the compass adjusted, but it cost £500 to adjust that compass. (laughter)

INTERVIEWER:

More than the adjuster’s fees! (more laughter)

CAPTAIN SLADE:

The adjuster’s fees at the time, I believe was £3 12s & 6d. (laughter)

INTERVIEWER:

Captain, the shipping depression was at its upmost depth in 1929, but you must have felt it coming on, and so on. What sort of steps did you take to meet it?

CAPTAIN SLADE:

It appeared that we'd got down to low water as far as we could go, and I'd got an expensive family to keep up, and it meant a lot of hard work for me in cutting the crew. Up to then we carried four hands, but I cut off two men, two young men, ordinary seamen, and got a man equal to the mate, so that we sailed her with three men in a way that we were sharing the wages of the odd man. I was getting extra, and the man that was shipman was getting mates wages instead of A.B.'s wages.

The mate I increased one pound a month, and I was also serving the food for one man. To do this of course we needed to have a motor winch. The motor winch saved a lot of work, heaved the anchors up, we'd had that for years but this time we couldn't manage without the motor winch.

INTERVIEWER:

You and your family were not the only people hit by the depression?

CAPTAIN SLADE:

Oh no. All the ships in Appledore were hit. All our vessels cut down to three men where they did have four and others of course followed suit. But we still could just manage to exist.

INTERVIEWER:

I imagine the town of Appledore itself felt the depression.

CAPTAIN SLADE:

Yes. The shipyards of course suffered with the ships and a lot of men had to be paid off. Mr Fred Harris and family (that's Messrs P.K Harris and Sons) they ran the yard and one day we were walking up there, and Mr Fred Harris said: “I don't know what I'm going to do. I shall have to close the yard. I can't get the work to carry on. I shall have to pay the men off."

So father said: “Well, I haven’t got a lot of money in hand and my family never run in debt. If they didn't have the money to pay their way they wouldn't have anything done." So my father said: "I'd like to have the HALDON stiffened up with bilge keelsons but the question is the money. I can't have it done unless I can pay."

So Fred said: “Well I'll come up aboard and see what can be done - see if we can put our heads together."

So Fred came on board and had a look at what father required. We had to raise her forward bow – rise her up nine inches back to nothing, to the waist of her, and put some nine-inch baulks in her bilge to the whole length, oak baulks. So he said: “I'll give you a contract for it."

When the price of the work came to father he turned round to me and said: “Its dirt cheap. I don't know how they can do it for the money." He said: “I can't refuse it. We'll have it done." We had that amount of money in hand so (I think the price about as far as I can remember was about 36 pounds). The men started work right away and Fred said: “Now I want you to do your best, this is a cut price and there's no profit."

Well they did their best, and it made a lot of difference to the HALDON and it kept the yard open another week, but I've often thought that Fred Harris was a good man for Appledore because he got nothing out of it whatsoever. His aim was to keep the yard going and give employment to the men that was in it.

INTERVIEWER:

Yes. A fine spirit of co-operation. There was some recovery in freights and conditions generally in 1939 prior to the outbreak of the war wasn't there?

CAPTAIN SLADE:

Yes. I think it was after the Munich crisis that freights went up a little. Probably about 20%, and we were able to get some money. Instead of just being from hand to mouth all the time, the money started to come in again. There was just that little bit that helped us along, and we carried on in the Irish trade all the time. All other trades was closed to us because the Dutchmen had taken it all. But we were doing very well.

INTERVIEWER:

When the war broke out, did that stop it at all?

CAPTAIN SLADE:

No. We carried on when the war broke out but what eventually seemed to put a brake on us was when the government made up their minds to lay a mine-field.

This of course they felt was a catastrophe because it was right in our track for the Irish side. I went down from Bideford one morning – I'd got chartered to go away from home to pick up the cargo from Lydney for Ireland – the first thing that happened, my father said to me: "If I was you, I wouldn't go. I'd stay home," and my cousin Dick was very perturbed about it. He was already home but he'd got the DONALD AND DORIS trading.

Well, I said: “Look Father, nobody will ever tell me that there isn't a lane somewhere down the Irish side. I'm going away." and I went away, and one of my cousins was anchored outside the bar waiting to go in loaded because he didn't know what to make of it, going across – about the mine field.

Well, as a matter of fact, I loaded my cargo, got the instructions from the customs as to where the mine field was, drew the mine field out on a chart, then I knew exactly the route to take.

So I made the voyage, got to Courtmacsherry alright and in the meantime my cousin had made up his mind that he would come down. When he came into Courtmacsherry I was on the way out and I wrote a message to him telling him that I'd rocketed the freight up (owing to the mine field), and to be careful what he was doing.

Well, I'd got my freight up to nineteen shillings a ton (from nine) through the mine field. That was my opportunity to raise the freights. I sent the message to my cousin and he did the same. So after that we carried on up and down the Tusker route you know, down inside the mine field and everything was alright.

INTERVIEWER:

Were you able to carry on with the Irish trade right through the war?

CAPTAIN SLADE:

Yes. We carried on all the way through and we did very well indeed with the Irish freights up as they were. But the time came when the government again put a spoke in our wheel. They requisitioned all the ships. Ordered them all to Appledore.

INTERVIEWER:

All the ships; then how did you dodge it?

CAPTAIN SLADE:

The telegram came ordering the requisition of the ship and ordering the HALDON to Appledore. I saw the mistake in the telegram: it was sent to my father – and father no longer owned the HALDON. So I ignored it and went on to Lydney to load the cargo back. I was looking for the big freight of course. When I got home by train - it happened to be neap tide, I couldn't get out of Lydney – the officer that had commandeered the ships was in Appledore.

All the rest were there, and I had to talk to him about the M A JAMES as I was an interested party, and he said: “Which is your vessel?"

I said: “Mine is the HALDON."

He said: “She's not here."

"No, (I said) she's in Lydney."

But he said: “I ordered you here."

I said: “Did you?" I said: “Are you sure?"

He looked up his book. "Yes (he said), I sent the telegram to Appledore."

I said: “Well I live in Bideford. You sent the telegram to the wrong man."

"Well (he said), can you get her here?"

I said: “No, she's loaded, besides (I said), I want something different from what you're offering. If I'm going to join the navy I want a commission! But I have other commitments and I'm not joining on an ordinary man's pay."

He said: “Well I think we'd better do without you."

I said: “Thank-you very much!"

INTERVIEWER:

That was one of your best days' work ever I should think.

CAPTAIN SLADE:

You bet it was! (laughter)

INTERVIEWER:

What happened to the requisition ships?

CAPTAIN SLADE:

They were dismantled, all the masts were taken out of them and they were to be used as balloon barrage ships in Falmouth and Plymouth. When they got round there, they put men in charge of them - to look after the welfare of the ships - that didn't understand anything about a wood ship, and the consequence was that they deteriorated very fast. When they were returned to us, they were nothing more or less than total wrecks.

INTERVIEWER:

And that was the end of the Appledore fleet of the old days?

CAPTAIN SLADE:

The bottoms of them was ate right out, and after a time – we had about 12 months arguing with the government about compensation – and they came to the conclusion that they were constructive total losses. As a matter of fact, I asked Mr Fred Harris of P K Harris & Sons, what t'would cost to repair the M A JAMES, and he said: "A thousand pounds. More than you're getting for her!" Seeing we'd had a raw deal all through – they paid a very small sum for them - the money wasn't in hand to find the odd thousand pounds, so I said: “Well I'm not laying any money out on it”, and we finished with it, with the same.

INTERVIEWER:

That was the end...

CAPTAIN SLADE:

That was the end of the vessels, they fell to pieces - at Appledore.

INTERVIEWER:

That's a very very sad end.

The HALDON ran right through the war, did she?

CAPTAIN SLADE:

Yes, she carried on right to the end, to the armistice, but I stayed home from sea a little while - perhaps two or three months – before the war ended. I had been in an air raid in Avonmouth, and got knocked about the head a good bit, and my eyesight was failing; I believe through the blow, and the severe strain on it.