Hide

The History of Patrington Church

hide

Hide

Hide

PATRINGTON:

The History of Patrington Church

Source=h:/!Genuki/RecordTranscriptions/ERY/YorksChurchesERY.txt

The church of

Saint Patrick

Patrington

Patrington.* Pattrington, or Patrick's town, is thus mentioned in Domesday :-

" In Patrictone, with four. Berewicks, Wistede, Halsam, Torp, Toruelestorp, there are thirty-five carucates and a half, and two oxgangs, and two parts of an oxgang to be taxed. There is land to thirty-five ploughs. The Manor is and was belonging to the Archbishop of York. There are now there in the demesne two ploughs and eight villanes, and sixty-three bordars, having thirteen ploughs.

* Patrington is a small market and post town, in the diocese of York, in the Archdeaconry of the East Riding, and in the Deanery of Holderness. It is about eighteen miles south east of Hull, and close upon the banks of the Humber. The drive from Hull is uninteresting, except to the ecclesiologist, who is amply repaid by the extreme beauty of the churches of Hedon and Patrington, with the less important, but not uninteresting churches of Keyingham, Ottringham and Winestead.

There are six sokemen with two villanes and twenty bordars, having five ploughs and a half. There are thirty-two acres of meadow there. Two knights have six carucates of the lands of this manor, and two clerks, two carucates, and three oxgangs, and the third part of an oxgang. They have there four sokemen and five villanes, and three bordars with five ploughs. In King Edward's time the value was thirty pounds, at present ten pounds and five shillings. Arable land three miles long and one mile and a half broad."

On this extract we may note, that the natural aspect and extent of the town of Patrington and its circumjacent territory, must have changed materially since the conquest ; for the encroachment of the sea on the Eastern coast, and the accumulation of sand within the mouth of the Humber,* has been destroying not fields only but whole towns and villages, for many successive ages. The tower of Patrington looks upon the site of the ancient town of Frismarsh, little more than a mile distant, now covered with sand ; and in 1637 a survey of the manor records that " as for our grounds near the Humber, we have lost much, and are every year losing more."

* The warp, or alluvial soil of the number, is, however, making tardy reparation for the mischief that it has done, by the formation of " Sunk Island," which has been gradually reclaimed, and is now a rich and well cultivated district, containing nearly 6000 acres. A church has been erected upon it, and it is formed into a distinct parish by Act of Parliament. A view of the whole district is commanded by the tower of Patrington church.

The most important information to be gleaned from the above extract from Domesday, is that Patrington had long been in the possession of the Archbishops of York ; and there are records which assert that it was to Athelstan that the Archiepiscopal see was indebted for the grant of this manor. Another document purports to be a copy of a grant from Canute the Great to Alfric, Archbishop of York, of this same manor : and though this is a century later than the reign of Athelstan, the two accounts are perfectly consistent; for the Dane may first have forcibly possessed himself of the property of the church, and then, for the redemption of his soul, and that of his father, restored the impropriation, as it is tenderly called in later times, to the true owners.

But in 1545 a more ruthless spoiler laid his hands on the fair manor of Patrington, which passed with many others to the crown. From this time, (with the interval of the great rebellion,) the manor of Patrington remained in the crown, and was held by different members of the Royal Family, until 1698, at least, when our Sovereign Lady Queen Katherine and her assignees, are officially recognized as holding the seigniory. Since that time it has passed through many hands, and is now vested in the Hildyards, of Winestead. Much ignorant vulgar abuse has been expended, (and the uninformed, if they be at the same time irreverent or unchristian, still fall into the same strain,) on ecclesiastics, or ecclesiastical bodies, as possessors of property, beyond (even if that may be allowed) a bare subsistence : and to hear some men talk, one should think that no clergyman was even anything but intensely selfish in all the uses which he makes of his benefice ; and that all the property of the church was so much absolute loss to the state and the people, to God and the poor.

There is no study, in its proper connexion with history, which will not abundantly refute such an unwarranted slander ; but ecclesiastical architecture, especially, abounds in proofs that the direct contrary to the popular prejudice is the truth. Let us take the case of Patrington as an example. Patrington, a manor erewhile of the Archbishops of York, has a church of surpassing beauty and grandeur, built obviously at one era, but without anything to mark the proud, selfish, and self-indulgent prelate, who, in all likelihood, raised it from the foundation to the topstone. A neighbouring church ; which we do not mention, because the blame is not so much to individuals as to the inveterate pride, selfishness, and irreverence of our nation; and which we need not mention, because similar instances will occur to every one :-affords a striking contrast to that of Patrington. It has fallen, for generations past, under the control of lay-impropriators, and accordingly it is a mere mausoleum, and a shabby one too, of the wealthy lords of an adjoining mansion, whose vaults, and tombs, and hatchments, and quarterings are all in all, in the structure and arrangement of the church. Surely the state, the people, and the poor are all benefited, and surely God is honoured by the munificence, though it be of ecclesiastics, which has erected such splendid churches as Patrington : and surely God is dishonoured, and the state, the people and the poor are defrauded, by the coarse and selfish appropriation of a house of God, however unpretending in its structure to the boast and display of the dignities and genealogies of men.

All our better feelings are excited as we enter the temple of God, and feel that to its founders at least God was all in all: but in spite of our kindlier temper, a severe judgment will suggest itself to us, when we see the holy edifice partially or wholly diverted from its purpose, and the honour of God yielding by degrees to the assumption of man. Such thoughts as these crowd upon us at such a sight, and we are compelled to say, in the bitterness of our hearts, How great people have occupied the adjoining hall and here repose! How small the mite of homage that is given by the living, in their own persons, or in piety to the dead, to that God, in whom both quick and dead are yet alive, and before whose awful presence the sanctuary ought to bring us ! The temple of the Lord, a mere place for recording and perpetuating the names and honours of the dead ! Nay, but even this is not all ; not only is the church but little honoured for its own sake, but the very mausoleum itself is the less cared for, because it is also a house of God. ` In that it is God's house,' says the pious son of twenty generations of recumbent ancestors, 'it is not mine : or the green and tottering walls should not moulder as they do, and look cold and chill upon my father's monuments?' Now to assume that any one would thus speak aloud, or even dare to frame the thought into words to his own ear were monstrous : but there are the facts, repeated in half a dozen instances within a mornings ride of almost every village in England: they must embody some deeply rooted habit of thought and feeling. They are the outward signs ;-a character committed to the form and permanence of marble, and to say that they represent nothing is palpably absurd.

And be it remembered that Patrington is no more a singular instance of the munificence, charity, piety, and self renunciation of some Ecclesiastic, than such a blot upon the land is of the --nay let some one finish the sentence, with a princely domain, whose tenants worship within his park gates, in a church overgrown with lichens, and with the water dripping through the roof. Every where the same thing is repeated. Every where the impropriated edifice ruined, or sacrificed to worldly aggrandizement : every where the traces of a finer, or at the least more religious structure, remind us of the piety or munificence of some ecclesiastic, or ecclesiastical body. But let us leave the more cheerless side of the contrast, and add, that the beautiful chapel erected by Bishop Skirlaw, in the same deanery with Patrington, forces itself on our recollection as an instance of episcopal piety to God and munificence to the poor. And before we leave the subject, we will just observe that in another point of view also the church of Patrington exemplifies the falsehood of such prejudices as we are here protesting against. It has been for upwards of a century in the patronage of a learned and Ecclesiastical Society,* and whether it be in consequence of this or not, yet certain it is, that it is in far better preservation, and has suffered less from barbarism of restorations or destruction, than nine tenths of the churches in the kingdom.

* Clare Hall, Cambridge.

But we must return to the subject more immediately before us.

The following list of the Rectors of Patrington is extracted from Poulson's Holderness. It will be found very incomplete in the earlier periods, but we presume that there are no materials to fill up the lacunae.

| Instituted. | Rectors. | Patrons. | Vac. by |

| 3 Ides Mar. 1303 | Dns. Wills de Tothill, Pbr. | Arch. per lapsum. | |

| Occurs in 1405 | William Betson. | ||

| S. Wm. Davyson, Cl. | mort. | ||

| 14 Feb. 1566 | Thos. Langdale, Cl. | SirJohn Constable, Kt. | The same. |

| 30 May 1587 | Humphrey Hall, M.A. | Assig. dni. Hen. Constable, Kt. | The same. |

| 22 May 1627 | Francis Corbett, M.A. | John Wright, gent. | |

| Occurs in 1661 | Samuel Proud. | ||

| 20 Feb. 1682 | Edwd. Saunder. | ||

| 1685 | John Pighills. | Death. | |

| 27 Nov. 1728 | Henry Hopkinson. | Master and Fellows of Clare Hall, Cambridge. | |

| 1734 | Nicholas Nichols, M.A. | ||

| 24 Oct. 1772 | Fleetwood Churchill, M.A. | ||

| John Tockington, B.D. | |||

| 16 May 1782 | Thos. Waddington, M.A. | ||

| 1790 | Edwd. Healey, M.A. | ||

| 20 July 1803 | John Mansfield, D.D. | Promotion of J. Mansfield. | |

| 18 July 1805 | John Mansfield, B.D. | ||

| 1838 | Rd. Henry Kitchingman the present Incumbent. |

The Rectory of Patrington, which is a manor in itself, is rated in the King's books at £22, and at £628 in the late Parliamentary Returns.

Beautiful itself, and the more remarkable for the extensive plain upon which it stands.

The Church

The Church of Patrington is the first and last object of Patrington. attention in tile town : and the admiration of the student of Ecclesiastical Architecture grows insensibly from the moment that he first sees the taper spire against the sky, of the last inspection that he gives to the elaborate details to the finished structure. Popular feeling, clinging still, with a latent appreciation, to beauties which the true Goths and Vandals of past generations have called monstrous barbarisms, has attested its admiration of this noble structure by calling it " The glory of Holderness" : and with still greater discrimination, Hedon and Patrington are coupled together as "The King and Queen of the Holderness Churches ;" Hedon being (or at least having been, for it is sadly destroyed by recent repairs) something superior in majesty, while Patrington is certainly pre-eminent in the grace and light proportions, which constitute a queenly beauty.

The Church of Patrington is the first and last object of Patrington. attention in tile town : and the admiration of the student of Ecclesiastical Architecture grows insensibly from the moment that he first sees the taper spire against the sky, of the last inspection that he gives to the elaborate details to the finished structure. Popular feeling, clinging still, with a latent appreciation, to beauties which the true Goths and Vandals of past generations have called monstrous barbarisms, has attested its admiration of this noble structure by calling it " The glory of Holderness" : and with still greater discrimination, Hedon and Patrington are coupled together as "The King and Queen of the Holderness Churches ;" Hedon being (or at least having been, for it is sadly destroyed by recent repairs) something superior in majesty, while Patrington is certainly pre-eminent in the grace and light proportions, which constitute a queenly beauty.

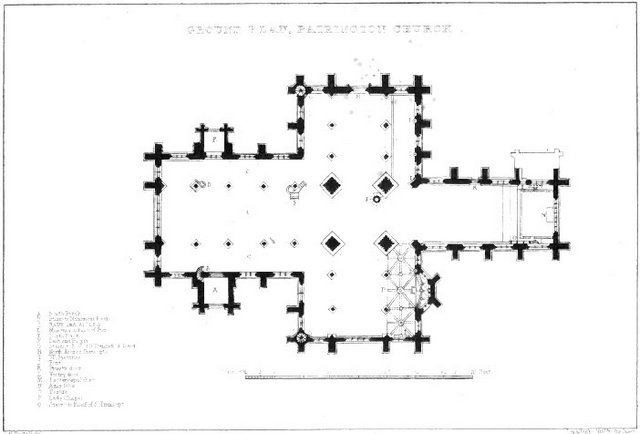

This elegant structure is of the most perfect style of Ecclesiastical Architecture, the Decorated,-and was probably erected late in the reign of Edward II., or early in that of Edward III. It is in the form of a Latin Cross, consisting of a chancel, a nave and aisles, north and south transept and aisles, with a Lady Chapel attached to the south transept, north and south porch, and central tower, surmounted with an octagon, out of which rises a lofty spire. Few churches are so uniform in their structure, or have received so few additions in a later style. It seems to have been begun and finished upon a well matured plan, while the decorated style was in its perfection, and the great East Window, which is perpendicular, is the only important insertion of a later date.

This elegant structure is of the most perfect style of Ecclesiastical Architecture, the Decorated,-and was probably erected late in the reign of Edward II., or early in that of Edward III. It is in the form of a Latin Cross, consisting of a chancel, a nave and aisles, north and south transept and aisles, with a Lady Chapel attached to the south transept, north and south porch, and central tower, surmounted with an octagon, out of which rises a lofty spire. Few churches are so uniform in their structure, or have received so few additions in a later style. It seems to have been begun and finished upon a well matured plan, while the decorated style was in its perfection, and the great East Window, which is perpendicular, is the only important insertion of a later date.

The value of this Church as an Architectural Study obliges us to devote two numbers to its illustration. In the present number we shall find enough to do to describe the

Exterior.

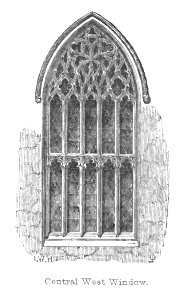

The West Front is divided into three portions, west Front. answering to the nave and aisles within, by buttresses of three stages running up through the roof, and terminated with foliated pinnacles. The central window is of five lights, and the head is filled with most graceful and elaborate flowing tracery ; but there are indications of an approach to the succeeding style both in the transom, which seldom occurs in decorated windows, and in a part of the tracery in the head of the window. If the eye is carried up along the line of the two centre mullions, to the head of the window, the line of the mullions will be found to be resumed by two perpendiculars near the top. Perhaps, too, the general flow of the lines may seem something more vertical than usual, though this is rather a matter of degree than of decided character. At all events this window is very beautiful, both in its proportions and in its details : though we regret to say that the lower portion, beneath the transom, is blocked up, being sacrificed to that Moloch of Church Architecture, and devourer of all lovely forms, a gallery within the Church.

The West Front is divided into three portions, west Front. answering to the nave and aisles within, by buttresses of three stages running up through the roof, and terminated with foliated pinnacles. The central window is of five lights, and the head is filled with most graceful and elaborate flowing tracery ; but there are indications of an approach to the succeeding style both in the transom, which seldom occurs in decorated windows, and in a part of the tracery in the head of the window. If the eye is carried up along the line of the two centre mullions, to the head of the window, the line of the mullions will be found to be resumed by two perpendiculars near the top. Perhaps, too, the general flow of the lines may seem something more vertical than usual, though this is rather a matter of degree than of decided character. At all events this window is very beautiful, both in its proportions and in its details : though we regret to say that the lower portion, beneath the transom, is blocked up, being sacrificed to that Moloch of Church Architecture, and devourer of all lovely forms, a gallery within the Church.

Corbel heads terminate the dripstones.

The Aisle windows on either side are of two lights.

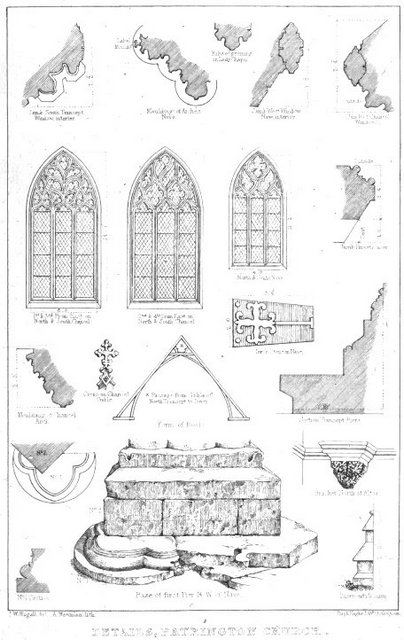

The buttresses at the angles of the West end, are continued through the whole of the exterior, with the addition of grotesque gurgoiles. The Aisles are thus divided into four compartments on either side, of which the second (reckoning from the West) is occupied with porches, the others with windows of three lights, and of pure decorated tracery.* The North Porch is of smaller dimensions than the South, but is furnished with buttresses at the angles, terminating, like the main buttresses of the Church, in crocketted finials. Above the South Porch is a chamber approached by a winding stair in the buttress, from the interior of the Nave ; and to this Porch with its parvise, one or two allusions well worth noting are found in the history of Patrington.

The buttresses at the angles of the West end, are continued through the whole of the exterior, with the addition of grotesque gurgoiles. The Aisles are thus divided into four compartments on either side, of which the second (reckoning from the West) is occupied with porches, the others with windows of three lights, and of pure decorated tracery.* The North Porch is of smaller dimensions than the South, but is furnished with buttresses at the angles, terminating, like the main buttresses of the Church, in crocketted finials. Above the South Porch is a chamber approached by a winding stair in the buttress, from the interior of the Nave ; and to this Porch with its parvise, one or two allusions well worth noting are found in the history of Patrington.

* See the Plate of Details.

" 1614, Patrington Manor Court. Mem.-That John Newton, without this court, the 28th day of Jan., 1613, before Stephen Blyth and Thomas Green, Trustees of the King's Majesty, Lord of this Manor, did surrender into his Majesty's hands all that his copyhold land, &c., to the use of John Duncalf, &c., with the condition that the said John Newton, his heirs, executors, administrators, or assigns, do pay or cause to be paid unto the said John Duncalf, his executors, administrators, or assigns, at one whole entire payment, the sum of forty pounds, of good and lawful money of England, at or before the five and twentieth day of March, which shall be in the year of our Lord God 1613, within the South Porch of Patrington Church, or the place where the said parish church now standeth. That then this present surrender to be void and of none effect."*

* This extract is copied from Poulson's Holderness, (to which the author of this and the following Number of the Churches of Yorkshire will have yet again to acknowledge his obligation,) the author adduces an additional illustration of the custom of chosing the Church, or the Church Porch, for transactions of importance, to give publicity to the deed. The same John Newton binds himself to pay £35 at or upon the Mayden Tomb in the Church of St. John, of Beverley, commonly called Beverley Minster.

It is almost needless to add that such cases are by no means uncommon ; that the contract of marriage especially, as distinguished from the marriage itself was commonly, and indeed always properly, made in the Church Porch.

Not less common was the use of the room over the Church Porch as a place of safe custody for records of public importance : though we hope that the additional purely secular use, to which, as we learn from the following memorandum, the parvise at Patrington was appropriated, was not so common.

" Mem :-That April 18, 1666, it was agreed by the inhabitants of the town of Patrington, with the consent of Mr. Samuel Proud, minister, and Francis Smyth, and Michael Pattinson, then churchwardens, that the Chamber belonging to the Church, over the South Porch, commonly called by the name of God-house, is a fitting place and also secure for the towne's books of records for to lye in, and to remain in the town chest : it being also a convenient place for the head juries to meet in about the town's business, and so to remain for future ages."

The North and South Transepts are nearly uniform in structure, though there is a door beneath the central window of the North Transept, and the Eastern wall of the South Transept, is broken by the apsidal projection of the Lady Chapel. For the rest, the North and South walls are alike, and fall into the same ternary arrangement with the West end of the Nave, being divided by buttresses, between which is a large window of four lights in the centre, and a smaller of two lights at the extremity of each Aisle. The central windows, like the great Western window, are transomed, but they are without any other approach to the perpendicular style. The North doorway is given in the margin; it is chiefly remarkable for the bold relief of the corbels supporting the angular canopy, and for the figure at the point of the arch. Our Blessed Lord appears in the niche holding up His hands, (in which as well as in His side and feet, the wounds are deeply marked,) as if to say to those who enter I am the door. The Lady Chapel appears in the exterior view at the beginning of this number. It consists of three sides of an octagon, the Northeast and South-east sides being pierced with windows of two lights. The projecting angles are supported by buttresses.

The North and South Transepts are nearly uniform in structure, though there is a door beneath the central window of the North Transept, and the Eastern wall of the South Transept, is broken by the apsidal projection of the Lady Chapel. For the rest, the North and South walls are alike, and fall into the same ternary arrangement with the West end of the Nave, being divided by buttresses, between which is a large window of four lights in the centre, and a smaller of two lights at the extremity of each Aisle. The central windows, like the great Western window, are transomed, but they are without any other approach to the perpendicular style. The North doorway is given in the margin; it is chiefly remarkable for the bold relief of the corbels supporting the angular canopy, and for the figure at the point of the arch. Our Blessed Lord appears in the niche holding up His hands, (in which as well as in His side and feet, the wounds are deeply marked,) as if to say to those who enter I am the door. The Lady Chapel appears in the exterior view at the beginning of this number. It consists of three sides of an octagon, the Northeast and South-east sides being pierced with windows of two lights. The projecting angles are supported by buttresses.

Poulson, in his Description of this Church, enumerates the designs of several of the gurgoils, which are however only such as one usually finds: "a monkey holding the mouth of a gaping lion: one, a man with a fiddle; another, a male figure holding a gaping lion's head ; another, a lion rolling out his tongue." " Some of the buttresses," he continues, " have full length human figures, which ill accord with the fastidious delicacy of the present age ; they are characteristic, perhaps, of the grosser ideas and ruder manners of the fourteenth century." But it will perhaps be better, and nearer the truth, to account for the hideous aspect of the figures on the exterior of churches, as compared with the more beautiful forms of the images within, by the principles of symbolism in ecclesiastical architecture; and to suppose that evil spirits, and hideous forms of wicked imaginations, and vices and sinful lusts of the flesh, are represented without the church, and often, as in gurgoils especially, flying out from the walls, away from the sacred edifice : while within are represented virtues and graces, the true ornaments of the spouse of Christ.*

*We admit, however, that there are difficulties in the way of this account, for sometimes the figures within are hideous, and even impure: [see the Introductory Essay to the late translation of Durandus:] but we suspect that this is almost always in churches or parts of churches of later date than Patrington.

The Chancel is supported by four buttresses on The Chancel. either side, with two at the angles of the East end, all of three stages, pierced by gurgoils, and terminating above the parapet in crocketted pinnacles and finials. The Eastern gable, like all those that terminate the four arms of the building, is surmounted by a cross. The four lateral windows on each side are of three lights, and decorated; the first and third, and the second and fourth being alike.* The noble East window of seven lights, we have already mentioned as the only feature in the whole edifice of decidedly perpendicular character. It will be far better understood by a reference to the plate, than by the most minute description.

* See Plate of Details.

The parapet throughout the whole edifice is without embattlements, or any other decoration but a simple moulding. A bold string course runs beneath all the windows, and a basement moulding round the whole of the Church.

The roof is covered with lead, and retains its original high pitch throughout the whole building. It is to this circumstance that Patrington Church owes one of its greatest beauties, when viewed as a whole ; for nothing but the great pitch of the roof could give unity to a design, which consists in a lofty spire rising from four arms of a cross, rather deficient than not in height. The smaller elevation of a pointed roof harmonizes better with a spire, and indeed with anything that draws the eye upward, than a roof higher in fact, but with a lower pitch. And perhaps we shall not be far wrong if we say that this principle was more generally applied in Decorated Architecture than in any other, before or after. The clerestory, which breaks the aspiring lines of the roof, seems to have been less frequently used during that period than at any other time ; and the roof rose therefore from the Aisles, over the piers of the Nave in an unbroken line, and at a very high pitch to the tower. The clerestory to a Decorated Church will generally be found to have been added in the era of the late perpendicular, and the process has been as follows. The roof having fallen out of repair, it has been removed, and the Nave piers surmounted by a few feet of wall, pierced with the clerestory windows, which support a roof of the same height at the apex with the original roof, but of course of lower pitch, as springing from a greater height. We are writing in a district abounding with decorated churches in which this process has been pursued. In none is it, or indeed could it be plainer, than in the beautiful still, but originally exquisite Church of Market Harborough, in Leicestershire. The spire is lofty, and requires the more aspiring line of the former roof to harmonize the whole composition, though in fact the top of the roof of the Nave is some feet higher than it was originally.

The Tower springs from the intersection of the arms of the cross, and is supported on four massive piers, it is of three stories, two of which rise above the apex of the roof. Of the lower of these stories, each side is pierced with one narrow light ; and round the upper story, which is the bell-chamber, runs an arcade of four arches on each side, of which two are pierced with square headed windows. The buttresses of the tower die in the wall at about half the height of the upper story, and the whole is finished with a plain parapet, like that which runs round the rest of the Church, and furnished with gurgoils. From the Tower thus terminated rises an octagon, supported by flying buttresses at the angles,* and finished at the top with a parapet and sixteen crocketted pinnacles, from within which the plain but elegant octangular spire rises to the height of 180 feet from the ground.

* It is almost needless to observe that no method of connecting the spire with the Tower is so beautiful as this, it is seen in its greatest perfection in the most beautiful spire in the Kingdom, that of St. Michael's, Coventry.

From the giddy height at which it turns, and the appearance of enterprize in the exploit of fixing or repairing a weather cock, there is no part of the Church more constantly than this the subject of careful, and as it were boastful record in parish documents; but few exceed in particularity of detail, that which records that " John Burdass pointed Patrington Church steeple in the month of July, and put up the fane on the 14th day of August, 1715. The iron where the fane hangs is 8 feet long, from the upper side of the top stone. The cross that is on the iron is 10 inches at each end from the iron. The top stone is two feet in diameter, and eight square, [i.e. octangular,] and every square is 9 inches. It overhangs 5 inches, and from the upper part of the storm-holes to the under side of the top stone is 12 feet, and the iron 6½ inches in circumference where the fane hangs."

All this is certainly business-like, but not more interesting perhaps, than the following passage of Hugh St. Victor, in his " Mystical Mirrour," in which he moralizes on towers, steeples, bells, and weathercocks.

" The Towers be the Preachers and the Prelates of the Church : who are her wards and defence. Whence saith the Bridegroom unto his Spouse in the Song of Songs : Thy neck is like the Tower of David builded for an armoury. The cock which is placed thereon representeth Preachers. For the cock in the deep watches of the night, divideth the hours thereof. With his song he arouseth the sleepers : he foretelleth the approach of day ; but first he stirreth up himself to crow by the striking of his wings. Behold ye these things mystically : for not one is there without meaning. The sleepers be the Children of this world, lying in sins. The cock is the company of preachers, which do preach sharply, do stir up the sleepers to cast away the works of darkness, crying, Woe to the Sleepers: Awake thou that Sleepest; which also do foretell the coming of the light, when they preach of the day of judgment and future glory. But wisely before they preach unto others do they rouse themselves by virtues from the sleep of sin, and do chasten their bodies. Whence saith the Apostle, I keep under my body and bring it into subjection. The same also do turn themselves to meet the wind when they bravely do contend against and resist the rebellious by admonition and argument, lest they should seem to flee when the wolf cometh. The iron rod, upon which the cock sitteth, sheweth the straightforward speech of the preacher ; that he doth not speak from the spirit of man, but according to the Scriptures of God : as it is said, If any man speak, let him speak as the oracles of God. In that this rod is placed above the Cross, it is shown that the words of Scripture be consummated and confirmed by the Cross : whence our Lord said in His Passion, It is finished. And His Title was indelibly written over Him. The ball (tholus) upon which the Cross is placed doth signify perfection by its roundness : Since the Catholick Faith is to be preached and held perfectly and inviolably : Which Faith, except a man do keep whole and undefiled, without doubt he shall perish everlastingly."*

* See Translation of Durandus, page 199.

The tower contains five bells.

The approach to the tower is somewhat arduous, and frightful to weak nerves. The staircase in the North-west angle of the North transept leads to the roof. Thence there are steps, within the parapet, leading to a door in the apex of the gable. This leads into a gallery through the rafters of the interior of the transept roof, too low to pass, except by bending almost double.* Thus the tower is gained, and by a similar passage along the rafters of the roof (but without any floor or handrail, which is provided to the customary way along the North transept) there is access to the roof of the chancel, nave, and South transept. Once admitted to the tower, the usual spiral staircase in one of the angles reaches the battlement at the base of the spire.

* This gallery is shown in the roof, given in the Plate of Details.

Such is the exterior of this beautiful Church. It would scarcely be worth mentioning that one of the pinnacles from one angle of the tower fell through the roof, during a tremendous storm on August 21st, 1833, but that it affords occasion to add, that a good deal has been done lately by subscription in the repair of the pinnacles, and minor details, throughout the building ; but that a much increased subscription, which, for the honor of Holderness, ought not to be withheld, would find abundant application.

Interior.

There is nothing in the general arrangement of the interior, which will not be better understood by a reference to the accompanying ground plan and views, than by any description. It will be seen at once that the Nave and Aisles are separated on either side by five pointed arches, springing from clustered columns. The capitals are richly foliated, and the arches are surmounted by mouldings springing from corbel heads. At the base of the first pier to the North-west there are appearances of materials having been employed from a more ancient structure ; which is perhaps the only hint that remains of the Church which the present magnificent edifice must have replaced. The beauty of the Nave and Aisles is greatly marred by the erection of a gallery at the West end. To this shameful incumbrance the lower division of the great west window is sacrificed, to the utter destruction of its fine proportions. This is the more annoying, because a better arrangement of the seats would have rendered the erection of the Gallery utterly needless. The Pues also are set up with as little feeling for the beauties which they obliterate as possible. Of the history of their introduction we copy the following notice from Poulson :-

There is nothing in the general arrangement of the interior, which will not be better understood by a reference to the accompanying ground plan and views, than by any description. It will be seen at once that the Nave and Aisles are separated on either side by five pointed arches, springing from clustered columns. The capitals are richly foliated, and the arches are surmounted by mouldings springing from corbel heads. At the base of the first pier to the North-west there are appearances of materials having been employed from a more ancient structure ; which is perhaps the only hint that remains of the Church which the present magnificent edifice must have replaced. The beauty of the Nave and Aisles is greatly marred by the erection of a gallery at the West end. To this shameful incumbrance the lower division of the great west window is sacrificed, to the utter destruction of its fine proportions. This is the more annoying, because a better arrangement of the seats would have rendered the erection of the Gallery utterly needless. The Pues also are set up with as little feeling for the beauties which they obliterate as possible. Of the history of their introduction we copy the following notice from Poulson :-

" A document without date, but of the time of James the First, (perhaps the date on the pulpit of 1612,) is still preserved, being ' a true memoriall and necessarie testymonie of all ye newe erected stalls in ye paryssche churche of Patryngton, buylded for the beautifyinge of ye said churche, and for ye conveynence of ye parysshyoners with the consent of the parsonne and churchwardens;' amongst the stalls on the south side the middle alley, were ` Imprimis one grete peue buylded upon ge rale costes and charges of the pish, wherein the parson, curat, clerk, and singing men are to syt in tyme of divine service, and the next pue was buylt by Humphrey Hall, clerke, for his wyf and children.' The freeholders appear to have erected the pews at their own private expense, ` for the use of themselves, their heyres and assigns for eu'more.' It appears on the authority of Mr. Edw. Saunder, the rector, ' that Sir Robert Hildyard, Knt. and Barrt. of Patrington, did upon the 19th of January, 1684, grant, give, and pass over unto his son, Capt. Robert Hildyard, two whole pues or closets in the southe parte of the cross alley in Patrington church westward, abutting and adjoyning on the southe alley."

It is almost unnecessary to remark on this record, that it is an additional instance of the ancient spelling of the word pue as justified in the " History of Pews," set forth by the Cambridge Camden Society; and also that it gives some indications of the lower taste of the beauties, and the lower feeling of the sanctity of sacred edifices, which must have come in before closets or pues could be even tolerated, much more admired. The closets in Patrington Church, which utterly annihilate all the grace of proportion, and all the effect of the piers, by cutting off the bases from the eye, were " buylded for the beautifying of the said churche :" and the use of them is not to kneel or to pray, but " to syt in time of divine service." The law and equity of congregational worship were equally set at nought. Freeholders have no right, and not even a faculty can give them the right, to erect in a parish church pues or closets for the use of themselves, their heirs and assigns for evermore. The only appropriation of such tenements permitted by law, is to dwelling houses, not to persons, their heirs and assigns. Equally illegal, of course, is the grant by Sir Robert Hildyard to his son of " two whole pues or closets in the southe parte of the cross alley in Patrington Church westward, abutting and adjoyning on the south alley," where we see the attempt to assign territorial limits to the assumed property, as if it were a part of the Baronet's hereditary domains, and might be defined by certain lines westward and southward, and certain abutments.

It were well that the law of pues should be better understood ; especially that the utter worthlessness of a faculty to establish personal or hereditary property in them were generally known. There is scarcely a church in England, the whole pueage of which some jealous Camdenian might not overthrow. This would be in most cases a bad thing to do, because it would excite much bad feeling ; yet if it were generally known that it could be done, men might not be so ready to build themselves closets in the Lord's House, which are liable to be swept away tomorrow with the rest of the lumber in the church.

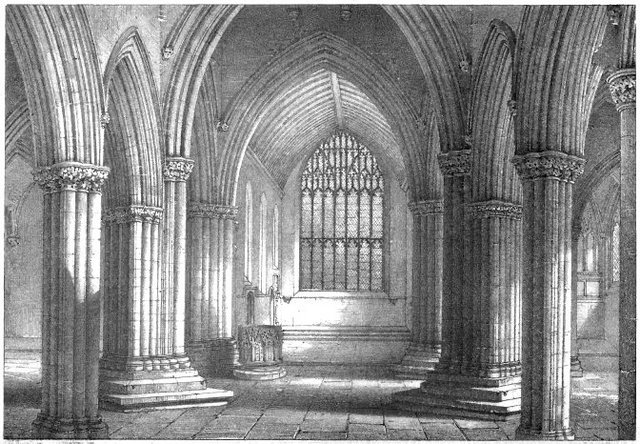

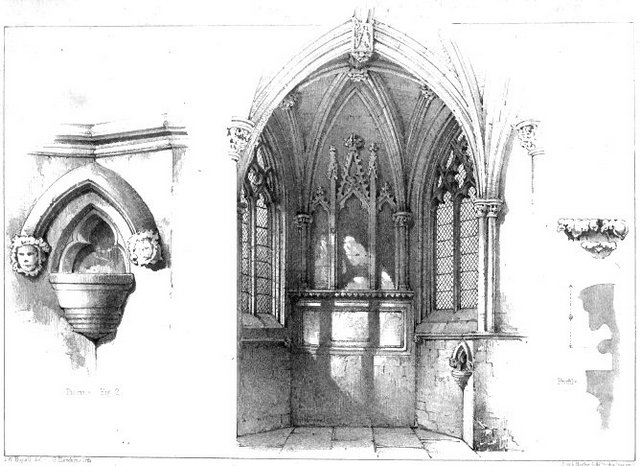

Four massive piers, each composed of twenty clustered shafts, support the tower arches. The capitals are adorned with foliage of the same character with those in the Nave. On either side, the Transepts, with their east and west Aisles, branch off from the Tower. Each Transept Aisle is of three divisions, and the piscina and bracket still remaining in each division, show that there were formerly as many chapels, and as many altars. The roof of the East Aisle of the South Transept is elegantly groined throughout; and the central bay with the addition of a three sided apse Lady Chapel. thrown out eastward, forms the beautiful little Lady Chapel. It will be seen, on reference to the accompanying drawing, that the two lateral divisions are pierced with windows of two lights ; while the central one is converted into a highly enriched altar screen, by the insertion of an oblong tablet, above the place where the altar stood, surmounted by three compartments of decorated tabernacle work. The oblong tablet is of a form most unusual in Gothic architecture, and in the present state of the chapel, with the altar and its ornaments removed, it is hardly congruous with the general character of the design ; but when the crucifix and the monstrance were surrounded with the tapers, and with the sacred vessels, as of old, that which is now somewhat inelegant, would be the best surface against which they could be presented to the eye. The details given with the Chapel are the upper moulding of the tablet, with one of the foliated ornaments that run along the top, and the piscina.

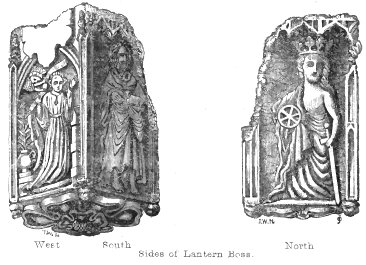

But the most remarkable feature in this Chapel, and perhaps indeed in the Church, for so far as we have had occasion to remark it is unique, is the central Boss,* which is formed into a pendant open on the Eastern side, so as to contain a taper which would throw its light down upon the Altar. The three closed sides are niches, within pointed pinnacles, containing sculptures of the Annunciation, of St. John the Evangelist, and of St. Catherine.  The latter figure, which is assigned to St. Catherine, on the evidence of her symbolical adjuncts, the wheel and the sword, is crowned, and occupies the North side of the Lantern : on the South side is St. John, clearly distinguished by the Holy Lamb resting upon a book which he holds in his left hand, while he points to it with his right; and under his feet appears what probably, in a more perfect state of preservation, would be recognized as the eagle, the evangelical symbol of the same Apostle. The Western side, or that from its position which is most prominent, represents the Annunciation, under the old ecclesiastical design of the Blessed Virgin at her devotions before a fald-stool, with the lily, the symbol of innocence and virginity, blossoming in a vase by her side, while the Angel appears addressing her from above. A scroll is descending from the top of the niche, which doubtless once contained the words of salutation recorded to have been uttered by the Angel Gabriel, which formed part of one of lectiones for the festival of the Annunciation.

The latter figure, which is assigned to St. Catherine, on the evidence of her symbolical adjuncts, the wheel and the sword, is crowned, and occupies the North side of the Lantern : on the South side is St. John, clearly distinguished by the Holy Lamb resting upon a book which he holds in his left hand, while he points to it with his right; and under his feet appears what probably, in a more perfect state of preservation, would be recognized as the eagle, the evangelical symbol of the same Apostle. The Western side, or that from its position which is most prominent, represents the Annunciation, under the old ecclesiastical design of the Blessed Virgin at her devotions before a fald-stool, with the lily, the symbol of innocence and virginity, blossoming in a vase by her side, while the Angel appears addressing her from above. A scroll is descending from the top of the niche, which doubtless once contained the words of salutation recorded to have been uttered by the Angel Gabriel, which formed part of one of lectiones for the festival of the Annunciation.

* By the liberality of Mr. w. D. Keyworth, sculptor of Hull, there are casts of this beautiful lantern, and of a piscine, brackets, the niche in the bead of the North door of Transepts containing a figure of our Saviour, and a portion of moulding in the Lady Chapel, in the collection of the Yorkshire Architectural Society.

The under surface of this elegant Lantern is formed into a rose.

In connection with the Chapels in the Church, we may mention that there was in the old Rectory House "a small building connected with the house in the North-east., an upper apartment commonly called 'The Chapel Chambre,' doubtless in former times an oratory, and in times more degenerate a brewhouse or scullery. In 1740, this interesting place was much injured by an hurricane or storm which continued nearly twelve hours ; but it still retained its original appearance until its final demolition in 1839. Near the South window was a well carved piscina, -and two conventual looking windows, with good mullions and transom, now in the possession of a person at Hedon. There is no question but an altar had been erected, and probably endowed here." *

In connection with the Chapels in the Church, we may mention that there was in the old Rectory House "a small building connected with the house in the North-east., an upper apartment commonly called 'The Chapel Chambre,' doubtless in former times an oratory, and in times more degenerate a brewhouse or scullery. In 1740, this interesting place was much injured by an hurricane or storm which continued nearly twelve hours ; but it still retained its original appearance until its final demolition in 1839. Near the South window was a well carved piscina, -and two conventual looking windows, with good mullions and transom, now in the possession of a person at Hedon. There is no question but an altar had been erected, and probably endowed here." *

* Poulson's Holderness.

In the South Transept is an unfinished gallery, or triforium, which appears in the drawing of the Transepts, approached from the tower by a ladder leading down to open steps, over the South tower arch. The arrangement is singular, and one wonders at the cool heads and steady feet of the ecclesiastics of earlier days, who found an accustomed passage among such galleries as this, and those along the rafters of the roof, whence they could communicate with the Lady Chapel, from the Nave or Chancel.

The Font is of one piece of granite, and is remarkable for its beauty, and still more so for its shape; being of twelve sides without, and circular within. We do not know of the existence of any other Font with more than eight sides. It stands under the tower, against the North-east pier. It is admirably figured in the " Illustrations of Baptismal Fonts," published by Van Voorst: a work of which it would be difficult to speak too highly.

A reference to the ground plan will show a considerable deflection from the right line in the Nave and Chancel of the Church, the Chancel declining very perceptibly to the South. This may be noted as the most refined application of the principle of symbolism to ecclesiastical architecture. The reference to the doctrine of the Atonement, and to the Cross of Christ, throughout the whole of the structure of every elaborate specimen of the mediaeval Church Architects is manifest. Not only do the instruments of the passion appear in many places ; not only do representations of our Blessed Lord upon the cross fill the windows of painted glass ; not only does, or rather did, the rood-loft extended across the Chancel Arch, midway betwixt the holy place and the holy of holies, shadow forth the cross as the way to heaven: but the great outlines of the foundation assumed the form of a cross, and to this was all the rest of the Church subordinated. But in some Churches, as in Patrington, the Chancel has a considerable inclination to either side, generally to the South, which is supposed to represent the inclination of our Blessed Lord's head, as he hanged upon the Cross. This inclination is almost always given in the ancient pictures of the crucifixion, and in crucifixes ; and it is therefore likely a priori, that it should be found in the other way so commonly adopted of representing our Lord's passion in the form of the Church ; and when this inclination is perceptible, we may reasonably refer it to this intention. Indeed where the inclination is sufficient to arrest the attention of one who stands at either extreme of the Church, it is a most fitting allusion to that position of our crucified Redeemer ; and cannot be referred to anything besides, with equal respect to our forefathers, with equal regard to probability, or with equal pleasure (and may we not add profit?) to ones-self. To imagine that it arose from the clumsiness of the Architects of the middle ages, as some persons would suggest, is monstrous. It is to suppose that the designers and executors of such fabrics as York Minster, or Patrington Church, had not the same power of following a right line, with the veriest clown that ever planted a row of cabbages in his cottage garden. But sometimes the deflection is not easily perceived, even when attention is called to it; and in such cases we can hardly refer it to a design of conveying any symbolical meaning: for this can only be done by a sign or symbol in itself evident to the senses. Besides, the necessity of the case may have sometimes led to such a peculiarity of structure, as in York Minster, where the builders could not, if they would, have carried the Choir in the same line with the Nave, on account of the foundations of a former structure.

Perhaps the author of this notice of Patrington Church may be allowed the opportunity to say thus much on behalf of a similar remark which he made in another work, and which has been somewhat lightly set aside by the ingenious and learned translators of the first book of Durandus, on Churches and Church Ornaments. To evade the symbolical allusion is altogether remote from his intention; he would much rather find it, and proclaim it wherever it is found : but this surely may be laid down as a principle; that the symbol must be easily seen at any rate, however difficult it may be found of interpretation. The meaning may be obscure, but the language to which it is committed must be sensible to the eye or to the ear, or there is no symbol at all. Now in very many instances the deviation of the line of the Chancel from that of the Nave is not easily perceived. Indeed the translators of Durandus themselves afford sufficient proof that the deflection is often utterly undiscerned, except by careful examination, and perhaps actual measurement, when they say that "there are many more churches in which it occurs, than those who have not examined the subject would believe ; perhaps it is not too much to say that it may be noticed in a quarter of those in England :" which is to say that it occurs in a vast number of cases, but so slightly that it has fallen to the lot of few even to suspect it. Now if it be necessary to account for this apparent irregularity of structure in such cases, may it not possibly have arisen, at least when the Nave and the Chancel are of different dates, which is very often, and indeed generally the case, from the custom of varying the orientation according to laws which seem to he for the present rather guessed at than determined.

Reverting, then, to the Church of Patrington, the deflection of the Chancel from the line of the Nave which in this is sufficiently conspicuous, seems to call us to the contemplation of our Blessed Lord in the attitude of suffering and weakness on the cross : and with these reflections we pass through the miserable modern screen, into the Chancel. And here we have, as in almost every case, to lament the hand of the spoiler. The noble East window is partially blocked up with the contrivance to contain commandments, a very common way in which puritans and antimonians have symbolized their opinion that the law is contrary to Gospel light. This window has also lost its painted glass; and its seven lights, and richly ornamented head no longer pour

Faith, Prayer. and Love."

The four graceful decorated windows on either side, are equally shorn of their tints, and of their

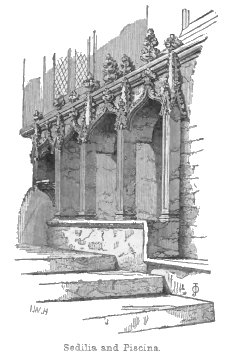

Whatever stall and screen work there may have been is also gone, but the decorations in stone are left more perfect than in most cases. There are brackets remaining on either side the altar, and in the south wall are three very graceful sedilia, and a piscina.

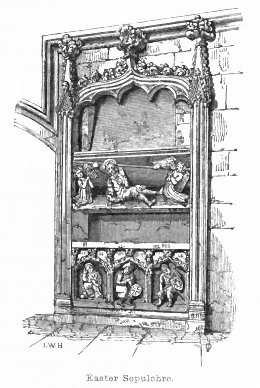

But the most remarkable part of the chancel is the Easter Sepulchre, which we never remember to have seen in any other church in so perfect a state. It is of four compartments, one over another, within a foliated and ogeed arch, flanked by buttresses having foliated pinnacles. The upper and third compartments are vacant. The second contains a representation in relief of our Blessed Lord's resurrection. He appears just rising from the tomb ; and two angels, one on either hand, are represented on their knees, waving their censers towards the figure of the Lord. In the lowest compartment, occupying as many niches, are three soldiers, watching at the sepulchre, in their attitude of fear, which the Evangelist describes : for fear of him (the angel) the keepers did shake, and became as dead men. The soldiers are of course represented in the dress of the time at which the sepulchre was erected. They have shields, with the following heraldic devices :-a lion rampant : a cross, and an eagle displayed with two heads. These are all of them common bearings, and it would perhaps be difficult to assign them to any particular families, even if a previous question were sufficiently determined :-how far, that is, we are to look on the devices upon shields which form part of the costume of figures introduced into ecclesiastical sculpture, as the arms of individuals. One would not think that a Christian Knight would choose to give his cognizance to one of the persons occupied in any act against the Redeemer: but it seems to be generally believed that some of the hideous, or otherwise unsavoury representations in ancient carved work are caricatures of individuals, brethren in the convent perhaps; and such representations would be scarcely accepted as compliments in the present day.* If such likenesses were introduced with the good will of the persons represented, the same tone of feeling would induce the gentleman of coat armour to lend his heraldic distinctions even to the watchers at our Lord's Sepulchre.

But the most remarkable part of the chancel is the Easter Sepulchre, which we never remember to have seen in any other church in so perfect a state. It is of four compartments, one over another, within a foliated and ogeed arch, flanked by buttresses having foliated pinnacles. The upper and third compartments are vacant. The second contains a representation in relief of our Blessed Lord's resurrection. He appears just rising from the tomb ; and two angels, one on either hand, are represented on their knees, waving their censers towards the figure of the Lord. In the lowest compartment, occupying as many niches, are three soldiers, watching at the sepulchre, in their attitude of fear, which the Evangelist describes : for fear of him (the angel) the keepers did shake, and became as dead men. The soldiers are of course represented in the dress of the time at which the sepulchre was erected. They have shields, with the following heraldic devices :-a lion rampant : a cross, and an eagle displayed with two heads. These are all of them common bearings, and it would perhaps be difficult to assign them to any particular families, even if a previous question were sufficiently determined :-how far, that is, we are to look on the devices upon shields which form part of the costume of figures introduced into ecclesiastical sculpture, as the arms of individuals. One would not think that a Christian Knight would choose to give his cognizance to one of the persons occupied in any act against the Redeemer: but it seems to be generally believed that some of the hideous, or otherwise unsavoury representations in ancient carved work are caricatures of individuals, brethren in the convent perhaps; and such representations would be scarcely accepted as compliments in the present day.* If such likenesses were introduced with the good will of the persons represented, the same tone of feeling would induce the gentleman of coat armour to lend his heraldic distinctions even to the watchers at our Lord's Sepulchre.

* But when a little church, lately erected in imitation of the Norman style, wanted heads fur a corbel table, it was gravely suggested that the clergy in a neighbouring town might be induced to perpetuate their likenesses, (it was not said how far they were to be distorted) in that form. The suggestion did not meet with the acceptance that its ingenuity deserved.

The Easter sepulchre is one of the appendages to ancient churches, most singularly connected with the highly imaginative, and we need not hesitate to say theatrical, services which had been already introduced, when the church of Patrington was erected. A consecrated wafer representing the body of our Blessed Lord, which had been in scenic representation entombed in the holy sepulchre on the night of Good Friday, was raised again in like fashion on Easter morn : and in all this the agency of more active personages than the carved figures beneath and above the tomb was required ; the clergy themselves taking their part, and representing, as is supposed, the several persons concerned.  This use of the sepulchre conciliated for it a very large measure of respect and ceremonial homage, and it was often elaborately constructed and adorned, though very seldom to the same extent with that which we have just described. Lights were burned before the sepulchre, as well as on the altar, and on the roodloft ; and it would seem that the prohibition against burning any other lights than the two which are still enjoined on the high altar was not always regarded ; and that while ultra-protestant parsons went beyond the injunction, in taking away the two that were to remain, those who disliked the reform movement retained some which ought to have been removed : for Archbishop Cranmer in his articles of Visitation in the Year 1547, asks whether the clergy " suffered any lights to be in churches, but only two lights on the high altar ?" and again, " Whether they had upon Good Friday last the sepulchres with their lights, having the sacrament there?" of course there remains no use for the Easter Sepulchre, under our more simple and primitive service ; but that is no reason why it should be converted, as we have often seen it, into a place for the tablet commemorating the virtues of some esquire of yesterday, or of his lady.

This use of the sepulchre conciliated for it a very large measure of respect and ceremonial homage, and it was often elaborately constructed and adorned, though very seldom to the same extent with that which we have just described. Lights were burned before the sepulchre, as well as on the altar, and on the roodloft ; and it would seem that the prohibition against burning any other lights than the two which are still enjoined on the high altar was not always regarded ; and that while ultra-protestant parsons went beyond the injunction, in taking away the two that were to remain, those who disliked the reform movement retained some which ought to have been removed : for Archbishop Cranmer in his articles of Visitation in the Year 1547, asks whether the clergy " suffered any lights to be in churches, but only two lights on the high altar ?" and again, " Whether they had upon Good Friday last the sepulchres with their lights, having the sacrament there?" of course there remains no use for the Easter Sepulchre, under our more simple and primitive service ; but that is no reason why it should be converted, as we have often seen it, into a place for the tablet commemorating the virtues of some esquire of yesterday, or of his lady.

On the north side of the chancel was a door opening into a vestry, now converted into a charnel house.

The roofs throughout the church are the original open timber roofs, of simple but elegant construction. They are given in the plate of details. Four large beams remain extended across the nave, and two in the north transept, below the roof, which have nothing to do with the composition of the roof, and somewhat detract from the beauty of the church. They are doubtless ties, rendered necessary by the absence of a tie beam in the ornamental portion of the roof. It is worthy of remark, also, that by careful inspection one may discover, in the chancel roof, a continued line of nails, projecting from the under face of each rafter; without any apparent use. But at the south end of the westernmost rafter there remains a small portion of moulding, and this was doubtless continued at one time through the roof, being attached to the rafters by the rails which have now lost their office.

Few such churches as that of Patrington are so totally devoid of monuments of any interest and beauty. There are a few insignificant brasses, and in the aisle is a stone lid of a coffin with the old and most happy device, the cross of calvary with a foliated head.* The transepts are disfigured with modern tablets, the greatest praise of which is to leave them nude-scribed. We cannot do better than give the following remarks from Poulson's Holderness, on the subject of such monuments. " There are numerous common place tablets and monuments in the Transepts, which, instead of contributing to the decoration of the fabric, are unsightly excrescences, and record nothing more than may be found in the parish register. Surely it would be better to perpetuate the memory of the departed, and to commemorate their virtues, if virtues they had to commemorate, by contributing to the repairs of a roof, or a tower, or a spire, or even removing one defect in this splendid edifice, the cold and comfortless glare occasioned by too much light, which can only be subdued by painted glass. The rich and mellowed hues of the storied pane,' would produce the glowing yet sombre effect which, no doubt, once was a characteristic of this Church." The volume from which this passage is transcribed, was published in 1841 ; and we cannot better acknowledge the help that we have received from it in the course of this description of Patrington church, than by thus adducing it as one of the first works which threw out so happy a suggestion for memorial windows, or other decorations, or additions to the church. Indeed we have found " PouIson's Holderness" far superior to most local topographical works, in the feeling with which ecclesiological subjects, (the most interesting by far, and the most important within their sphere) are treated.

* See the Sheet of Details.

Glad indeed shall we be to hear that the hint has been carried out in this case. There are but scanty traces of stained glass, throughout the church, and it is wanted every where, and every where the architecture of the windows is beautiful, and would display it to the best advantage; yet we cannot express a wish that in the present state of this art, so beautiful a structure should be supplied with painted glass, without adding that very great care should be taken that the glass, if bestowed, should be worthy of its destination. There is a meagreness and a glare of colours, bright but not rich, raw and unsubdued, in all but the very best windows of the present day, which loudly ask for some attempts on the part of those who have opportunities to study the subject, to improve on the present methods of preparing painted and stained glass. The very trees may be seen waving behind the gaudy and flimsy picture, or pattern, as it is now managed. The glass wants thickness as well as colour, and translucency rather than transparency. To cry out " We cannot imitate the old glass," and to repose in the indolence of despair is absurd. The real truth is, there is not yet a sufficient inducement to ordinary artists in glass to attempt it. To a careless eye, the bad substitute of the market is finer and brighter than the old rough looking material; and at present there are not enough who are dissatisfied with what actually pleases the many, to create a demand for anything better. It is perhaps too much to expect that the attempt should be made by those who are already abundantly occupied in supplying the inferior article now in request : and any interference on the part of an individual, who may want at the most some two or three hundred feet of stained glass, would be too insignificant to be attended to. But the Architectural Societies might take up the subject, and by their influence, more than by their patronage, make the production of glass worthy to fill the exquisite tracery of our old windows, worth the while, not merely of the two or three persons who are now worthily engaged in it, but of so many artists that there may be a fair competition. Where we have the motive to apply them, we are inferior to the middle ages neither in science, nor in ingenuity, nor in art; only let us turn our energies and acquirements in this direction, before more windows are spoiled by the present " Brummagem" systems of glass painting and staining, and we need not doubt of our success.

We may add perhaps a few suggestions on the repairs and improvements loudly called for in Patrington church. Those which are really necessary are chiefly connected with the roof, which cannot be thoroughly repaired but at considerable expense. The patronage is in a learned and ecclesiastical body, and it is perhaps not too much to say that to call attention to the need, is sufficient to have it not only done, but done as it ought to be.

The removal of the huge reredos, if such it can be called, painted with the commandments, and of the pues, closets and galleries throughout the church, with the substitution of open seats, would be so very great an improvement, that we cannot but hope that it may ultimately be effected by the good taste and good feeling of the little town of Patrington. It would be a noble application of a sum which would really require some little self sacrifice to expend on the church ; but the truly religious are at once ready to say, so much the better.

In suggesting repairs, we of course feel that we are speaking practically, and with hope that it may be done : and we close our account of this noble church with a cheerful assurance, that even in the description of its beauties and dimensions we are also speaking practically, and with a hope that the time is not far distant, when such models shall really be sought for, by those who are erecting new churches. The greater munificence and the greater taste now springing up in happy combination, may well suggest this glad anticipation. The dimensions of the church are as follows :-

| Ft. In. | |

| Height of Nave and Transept | 24 6 |

| Height of Chancel | 26 0 |

| Height of Nave, Transept, and Chancel, to the ridge of the Roof | 45 0 |

| Height of the Tower | 84 0 |

| Height of Tower and Spire | 180 0 |

| Height to top of weathercock | 189 0 |

| Interior. | |

| Ft. In. | |

| Length of Nave | 52 0 |

| Breadth of Nave | 38 2 |

| Length of Transept | 86 0 |

| Length of Chancel | 50 0 |

| Breadth of Chancel | 21 1 |

| Breadth of Transept | 39 2 |

| Height of pillars | 12 8 |

| Height of Arches | 18 8 |

| Total length of the Church | 141 2 |

The substance of this description of Patrington Church was communicated to the Yorkshire Architectural Society in a paper by the Rev. Geo. Ayliffe Poole.

Colin Hinson © 2019

from

The Churches of Yorkshire

by W H Hatton, 1880